Happiness is an elusive concept. Although it is studied by many, we are no closer to unlocking its mystery. Why is this? Can humans even define happiness well enough to chart a concrete path to its achievement? Though seemingly impossible, humans have continued in their attempt to outline and define what exactly happiness is, and how we can achieve it. One such quest lies here at Harvard.

Students searching for the pursuit of happiness might go back to the Ancient Greeks in search of a sound definition. Aristotle and Plato argued that intellectual ambition is the key to permitting true human flourishing. Rather than being governed by emotion, one should use reason as their guide in all decision making. Pursuit of knowledge and virtue, they argue, are keys to happiness. If that is the case, shouldn’t Harvard students be the happiest? Maybe not.

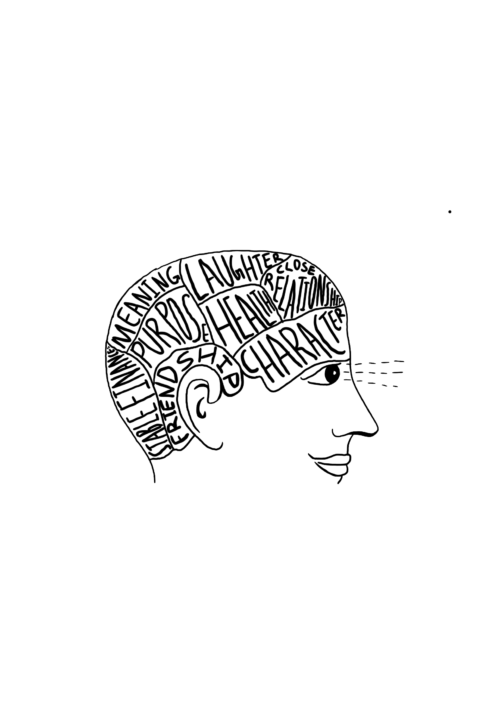

Beyond the scope of Ancient Greek rhetoric, the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science’s Human Flourishing Program is developing a new view on happiness. According to Program Director Tyler J. VanderWeele, happiness is an arguably narrower concept than flourishing, a more holistic measurement. Indeed, Dr. VanderWeele argues that while happiness is part of human flourishing, it only captures a small fraction of it. While happiness is a “positive affective state,”the working definition of flourishing at the Human Flourishing Program is “the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good.” In addition to the inclusion of happiness, The Human Flourishing Program qualifies happiness as a measurement of “health, meaning and purpose, character, close relationships, [and] financial stability.” Flourishing is not just growth, but growth into a better version of oneself. The program’s flourishing index is a contemporary version of what the Greek philosophers defined as the active journey towards knowledge—more particularly, knowledge of oneself.

So how do Harvard students fare with the Human Flourishing Index? Being completely satisfied is difficult. At Harvard in particular, the ceaseless overloading and overachieving makes satisfaction seem impossible. It’s easy in Harvard Yard to approach life with a “glass half empty” rather than a “glass half full” approach. Imposter syndrome is a real thing, especially on a campus where you can’t help but feel overwhelmed—by the ample opportunities to pursue, but also by the incredible accomplishments of peers that urge you to take on more challenges.

Researchers with the Global Flourishing Study have found that happiness and life satisfaction tend to demonstrate U-shaped curves: the youngest and oldest people are generally happier, while middle-aged people are less-so, likely due to career challenges, starting families, etc. More so, the left part of the U curve has been flattening, indicating that young people are not as happy as they used to be. If achieving happiness is becoming more difficult, how can Harvard students seek out happiness?

Close social relations are a measure of flourishing that appear to be common denominators among students. Junior Tommy Barone ’25 emphasized the importance of balancing career goals with happiness, stating that he guards time for pursuing only those passions that are most fulfilling to him, and those that he is sure are directly benefiting the lives of others.

Not only is it important for students to pursue activities meaningful to them, but it is equally important for them to share those moments with others. Junior Reza Shamji ’25, one known to brighten a room with his cheerfulness, reiterated this sentiment, stating that “inclusivity is one of the best parts of life.” For Shamji, sharing moments of life with others is how he pursues happiness. Inclusivity, he believes, permits people to uncover new perspectives and find joy through the discovery of new people, cultures, places, and activities.

As demonstrated by Shamji’s value of personal connection, it’s human nature to rely and depend on others for the fulfillment of genuine happiness. Sophomore Mitchell Callahan ’26 attributes his father as the key to his happiness; weighing each life event, good or bad, against the things that truly matter in life. He explains that by putting the small problems into perspective, we become grateful for what we have, and we never see ourselves as ever having major problems, thereby experiencing less stress.

While sharing moments with others permits happiness, oversharing also leads to harm. Even Dr. VanderWeele noted that some of the best studies have indicated that social media detracts from well-being and leads to higher levels of depression and anxiety. Social media has revolutionized happiness, allowing us to instantly compare our perceived levels of happiness to those of others for the first time in human history. We have access to unlimited amounts of gratification—a like on instagram, an overnight purchase on Amazon, a laugh at a fifteen second TikTok. In this environment, it is easy to see how one could confuse temporary joy with true happiness. While social media does not necessarily lead to this facade, the temporary displacement of face-to-face engagement and relationship formations can trick our minds into thinking we are truly happy.

It is clear that Harvard can be a wonderful place for students to flourish. Harvard can enable students to grow their learning, knowledge, capacity for critical thinking, and more importantly build strong relationships. Prioritizing one’s most important relationships is both gratifying in the short term, and vital for wellbeing in the long term. Certainly problem sets and long nights in the library may contribute to momentary unhappiness, but it is precisely in embracing such a challenging and stimulating environment with others that we can work towards flourishing together.

Alexandra Dorofeev ’25 alexandradorefeev@college.harvard.edu and Alice Khayami ’25 alicekhayami@college.harvard.edu are on a journey to become happier.