“Tell us about your first time.”

It always happens when we’re playing Hot Seat or Truth or Dare. Everyone buckles up for a good story—bonus points if it happened somewhere crazy. I smile softly to myself, knowing they’re going to be surprised, or maybe even disappointed, by my response that I’m a virgin and waiting for marriage.

I always knew sex was a big deal. In high school, when my friends started having it, I’d listen intently to how it affected their relationships. Everything changed once we started having sex, they’d say. Beyond the logistical fears I had—pain, pregnancy, and the horror of cherry-popping—I began to realize that sex had the power to change the course of a relationship. How compatible two people are in bed, whether they’re able to pleasure each other, can make or break it.

Thankfully, I never really had to worry much about it. Dating wasn’t a part of my life until college, so before coming to Harvard, sex wasn’t really on my mind. It was something my friends did and something that made for interesting stories, but it was not something I was concerned with. I don’t think I considered it inevitable, nor did I think critically about whether or not I would sleep with someone if given the chance.

Then, when I got to college, everything changed. I started dating, and I began to more seriously examine my moral values. I was struck, and a little bit scared, by the world of casual sex: Irish exits from parties, sleeping with strangers, being “exclusive” or “hooking up” without dating. I realized quickly that for most other women I spoke with, this was the exclusive definition of sex-positivity: something that requires being sexually active to display control over one’s own sexuality and comfortability with sex.

There’s a lot of good done in the modern sex-positivity movement. Intimacy is such a personal concept, and how a person chooses to go about their sex life should be received without shame or judgment. Moreover, a modern sex-positive attitude includes plenty of safety-focused concepts such as consent, open communication about sex, and sex education, all of which can contribute to a more supportive environment, particularly for adolescents and young adults just becoming comfortable in their bodies and sexualities.

For some, casual sex feels empowering. It’s no surprise that with the right boundaries, consent, and open communication, hookups are all the rage. The issue is that this seems to be the only collegiate definition of “sex-positivity.” According to the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 94% of college students are sexually active. So where does that leave those of us playing the long game?

The answer, sadly, is lumped in the “purity culture” category. Purity culture refers to a harmful mindset around sex which first gained popularity with evangelical Christians but has spread to secular culture as well. It is the idea that not only is premarital sex sinful, but also the brunt of the responsibility is on women to suppress their sexuality and practice modesty in order to protect men—whose sexuality is seen as much more acceptable—from falling into sin. Purity culture is often weaponized against women who have engaged in premarital sex and can be used to create an atmosphere of shame surrounding sex education, including important conversations about consent and women’s health. Unfortunately, this is what many people associate with waiting for marriage.

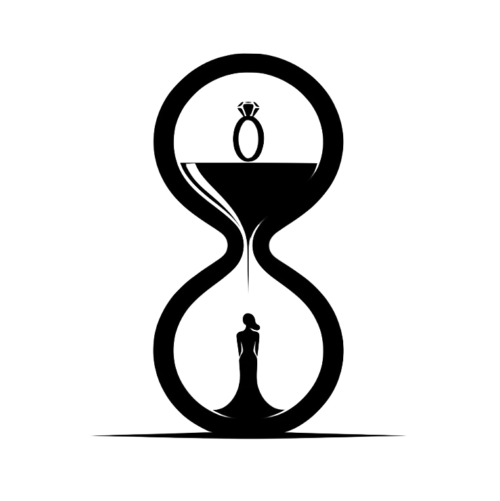

But the truth is, chastity doesn’t have to look that way. I am waiting for marriage, because I believe sex is a way for two people to give themselves to each other, fully, which is essentially the promise of marriage. To me, it makes sense not to say to someone, I give myself to you, entirely, with my body, before saying it to them out loud. And contrary to popular belief, virgins can still have deep understandings of their own sexuality. Though I am not currently sexually active, I am in charge of my own sexuality. I am comfortable talking about sex. I know what it means to me and what I want it to mean to the person I someday marry.

Just as sex-positivity can mean casual sex, or sex while dating, I argue that so too can it mean chastity. Choosing to wait for marriage doesn’t make you a prude, or out of touch with sex—rather, it can be an informed decision tethered to a deep understanding of sexuality. Let’s broaden what we mean by sex-positivity to a definition that includes virginity along with being sexually active, and equally empower those of us who choose to wait.

Written Anonymously for the Harvard Independent.