Open up Instagram, and you will likely see a college athlete promoting one product or another, whether it is Livvy Dunne sporting the newest Vuori set or Paige Bueckers using CeraVe face wash in her latest get-ready-with-me video. However, it is not just the most high-profile college athletes making money off of their name, image, and likeness (NIL). Harvard athletes are also embracing the lucrative possibilities of NIL, and experiencing challenges and success as they navigate the changing world of college athletics.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), which governs college sports in the U.S. and Canada, long defended the principle of amateurism and used it to justify prohibiting college athletes from earning money for anything related to their athletic endeavors. This meant that, for decades, college athletes could not profit from their name, image, and likeness while competing for their schools.

The change to the NCAA’s NIL policy was relatively abrupt. After states began passing legislation, like California’s 2019 “Fair Pay to Play” Act, to prohibit schools from punishing collegiate athletes for accepting endorsement money, pressure on the NCAA to reform its policies increased. The NCAA began planning changes as early as 2020, but the Board of Directors did not introduce new rules until July 1, 2021, after the Supreme Court ruled against the NCAA in Alston v. NCAA. The case made it clear that the organization would face lawsuits and other legal challenges if they continued to restrict athletes’ ability to capitalize on their name, image, and likeness.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, when the NCAA suddenly conceded athletes the right to earn money from their NIL, its new rules were woefully inadequate. They stated that athletes were permitted to receive compensation for the use of their NIL as long as deals were not performance-based, ie. pay-for-play, or used as recruitment devices. However, the NCAA offered very little guidance on how to regulate these new activities and shifted responsibility to states and schools to establish their own NIL policies.

Collectives, which assemble large and small donors to give money to a school’s athletes through NIL deals, have formed at universities and taken advantage of the NCAA’s loose rules by stretching them to their limits. Although athletes purportedly perform services, like signing autographs and appearing at events, in return for the collectives’ payments, the activity has slipped suspiciously toward performance rewards and attractive tools to recruit high school prospects and lure transfers from other college programs. Indeed, college athletes are transferring at an unprecedented rate in search of greater NIL opportunities. Additionally, some older international athletes are now competing against kids fresh out of high school in college competitions because they can earn more from NIL than from running professionally where they are from.

In the absence of a federal law regulating NIL, around 30 states have enacted their own distinct laws. For example, some states, like Florida, require athletes to disclose proposed NIL contracts to their schools before finalizing them; others, like California, do not. Some states prevent students from endorsing certain products, like alcohol or gambling, while other states allow schools to require athletes to pool and share their NIL earnings among themselves. This highly variable patchwork of laws has led to an unequal playing field for college athletes seeking to profit from NIL around the country.

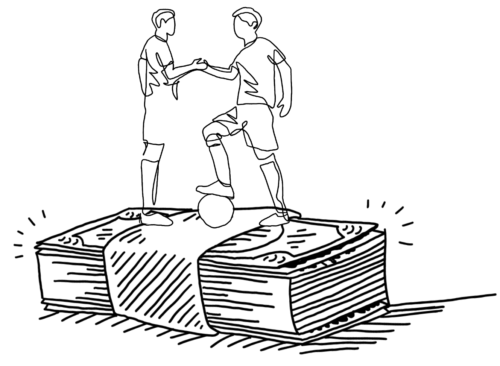

Many have celebrated the reformed NIL policy, which has given student-athletes the opportunity to receive compensation for their historically undervalued services, which have generated billions of dollars of revenue for their institutions. Male and female athletes alike, in both highly visible and less watched sports, are earning money. Many athletes who might have previously left college early to pursue lucrative professional deals are staying put, happy to make money while representing their schools and receiving a valuable degree.

Yet the NIL riches are not being evenly distributed. Out of the $1.7 billion projected to be spent in NIL transactions this year, the vast majority of it will go to Power 5 conference male football and basketball players. These deals typically fall in the five-figure, or sometimes even six-figure, range. Smaller schools simply cannot compete. Additionally, because collectives can now direct money to individual athletes rather than athletic departments, budgets for non-revenue sports with less visibility and women’s programs are falling, even at big universities.

As part of the Ivy League, Harvard faces a somewhat different set of challenges regarding NIL. Already unable to offer athletic scholarships, Ivy League schools may find it even more difficult to attract top recruits when collectives at other schools are offering large NIL deals. Moreover, as Ivy League competition tends to have less national prominence and visibility, athletes may have smaller audiences and therefore less marketing power when negotiating partnerships with brands.

Harvard student-athletes credit the school with making it relatively easy to secure NIL deals, as their sole responsibility is to submit contracts and documents through an app called “Influencer.” However, where other universities have staff that helps facilitate NIL deals for individual athletes or entire teams, Harvard does not. Harvard’s official NIL policy states, “Harvard coaches, faculty, staff, or other individuals employed by or contracted with Harvard may not be involved in the development, operation, arrangement, direction, or promotion of any non-university NIL Activity.”

Harvard athletes may only in limited cases endorse entities that compete with Harvard official sponsors, and they may not promote “products or services that are illegal, or conflict with institutional values of policies,” like gambling, alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana products. They may not use Harvard University’s name, insignia, or other identifiers in their promotions, nor can they use photographs or film of Harvard’s facilities and campus landmarks. Before finalizing any NIL deals, Harvard athletes must disclose the contracts to the Harvard Athletics Compliance Office for review and approval.

Despite these obstacles, several Harvard athletes across a wide range of sports have entered the NIL market, and they have done so in a variety of ways. Off the back of a remarkable fall season his junior year, in which he broke the NCAA record for a men’s 5000-meter race and achieved the Olympic standard, Graham Blanks ’25 of Harvard cross country and track and field signed a major NIL deal with New Balance.

Blanks relied on an agent who reached out to his coach before the season to negotiate the deal. His contract, unlike professional ones, does not include any performance-based stipulations; he is simply required to make a certain number of event appearances, and New Balance may use his name, image, and likeness however they see fit in their advertising campaigns or on social media. In return, Blanks gets paid a substantial sum and receives free gear to train in—but not to compete in—as Harvard requires him to wear the school’s sponsor Nike in official collegiate races.

“It’s good to establish relationships at a brand,” Blanks, who plans to run professionally after college, said. “It’s nice to get your foot in the door… It’s almost like early recruiting for professional running.”

Previously, Blanks would have been unable to work with an agent, as signing with an agency is prohibited under NCAA regulation. However, athletes are allowed to use agents for the purposes of making NIL deals. Through this provision, Blanks has built a relationship with an agent from the prominent Flynn Sports Management, which he believes will be invaluable as he enters the world of professional running, where agents are critical to securing spots in the biggest competitions.

In addition to his New Balance deal, Blanks also reached out personally to partner with Jittery Joe’s Coffee—a local coffee roastery in his hometown, Athens, Georgia—whose coffee he has brewed for years in his dorm at Harvard. The financial support from New Balance has afforded Blanks the advantage of not needing to pursue additional NIL deals solely for financial gain. Since he was never particularly active on social media, he was not inclined to endorse numerous products. This has allowed him to concentrate on collaborations such as the one with Jittery Joe’s, where they launched a new coffee can featuring his face. He said, “[The deal] was really cool, just because I really like the company, so it’s just neat to have my own can.”

Other Harvard athletes have established NIL deals through other avenues. Lennox London ’26 on the Harvard women’s rugby team started taking advantage of NIL opportunities through the organization 98Strong, which matches student-athletes with different brands.

London’s first experience promoting a brand was with Olipop; she created a post with a few different pictures and earned between 50 and 100 dollars. Although she had fun, the biggest challenge for her was coming up with creative ways to promote the products. “I would love to do more deals. I just kind of figured out that I’m not very good with content-creating,” she said.

London discussed the difficulties of earning NIL deals when competing in a sport with less visibility. “I think if rugby…was more popular, and people in America cared more about female rugby athletes, I think it would be really cool to capitalize on the NIL stuff,” she said. “I know that’s changing right now, but it’s kind of easier for a track or a soccer athlete to get NIL deals because people care about that more.”

London is neutral on whether attending Harvard has helped or hurt her in the NIL market, but Blanks is convinced that Harvard’s brand has given him an edge. “Being a Harvard student…signals you do have other passions, maybe outside of running, which makes you a little more interesting,” he explained.

However, Blanks also pointed out that while Harvard has supported his NIL efforts, the school could push boundaries further. “Harvard isn’t really doing anything in terms of the big NIL stuff that Power 5 schools are doing, where you’re giving back to the athletes through different ways, like boosters or merchandise or anything like that,” he said. “It would be interesting to see Harvard maybe try to be a little more progressive [and] adopt this new NIL stuff, because they’re kind of going to have to, if they want to remain athletically competitive.”

Both Harvard athletes agree that the NCAA’s reformed NIL policy has opened up doors for collegiate athletes around the country. “I think it’s great that athletes can capitalize on their NIL,” said London. “It gives you more control over your representation because someone’s making money off of it, so it should be you, because…it’s your name, image, or likeness.”

Nevertheless, change can be uncomfortable. Blanks spoke about the value college sports have had in the U.S. in the past. “I think the NCAA is special just because you combine a college education with getting to represent your college athletically. I think that’s super unique,” he said. “Maybe I would have reservations about trying to over-professionalize it…a little too quick with the NIL stuff.”

Ultimately, the introduction of NIL marks a transformative period in collegiate athletics, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. Harvard athletes like Blanks and London illustrate the ways in which student-athletes are navigating this new landscape—balancing financial gains with academic and athletic commitments. However, the half-baked regulations and the dominance of Power 5 schools highlight the need for more standardized policies that ensure equity and fairness across institutions and sports.

As NIL continues to evolve, the NCAA stands at a pivotal crossroads. The decisions made in the coming years will determine the sustainability of NIL and redefine the student-athlete experience. Ivy League schools like Harvard must find a balance between upholding academic integrity and accepting some degree of the commercialization of athletics. The path forward demands thoughtful solutions that will empower and enrich athletes while preserving the joy of college sports.

Gemma Maltby ’27 (gmaltby@college.harvard.edu) plays on the Harvard women’s soccer team and would love to make some NIL money.