In a society that celebrates overworking and rewards all-nighters, the pressure to always be productive has become inescapable. From calendars packed with back-to-back meetings to libraries thriving at 2 a.m., the push to do more is always there. Especially at Harvard, where boasting how much you overwork and how little sleep you are getting is like a badge of honor, the idea of taking time to rest can feel like a radical act. Reclaiming our right to rest becomes more than just an act of self-care; it becomes a form of rebellion against a culture that promotes self-exploitation.

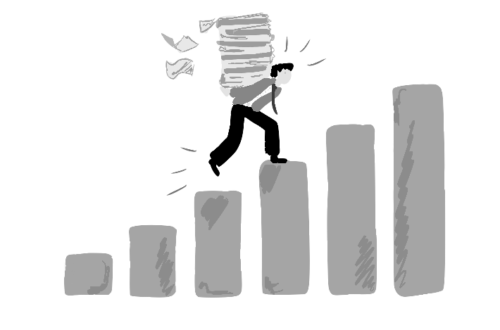

Every individual living in a capitalist society seems to have to face the pressure of exploiting oneself. The demands of the system are never-ending: emails piling up daily, meetings stretching into the evening, endless late nights working at the library, and weekends becoming an extension of the work week. The relentless pursuit of productivity over everything, a fundamental characteristic of this system, has led us into a cycle of self-exploitation. But we must resist—we must defend our right to rest by accepting that doing nothing is not only acceptable but necessary.

To understand where this culture of overwork and self-exploitation comes from, we first need to talk about the structure of our current economic system: capitalism. Capitalism is structured around the premise of the maximization of productivity and profit over everything else, even over human life or nature. In this system, success is measured by the continuous accumulation of wealth, and often, it is never enough. Therefore, for the system, the only value that people have is their ability to produce and contribute to economic growth. This might sound productive and logical at first, but in a system that values profit over anything, it means that people often get reduced to a mere means towards the ultimate goal of profit. Moreover, capitalism relies on a workforce that constantly produces and consumes. Thus, the emphasis on productivity and the negligence of well-being is a fundamental feature of capitalism since it relies on it to survive.

For many, especially at an institution as competitive and prestigious as Harvard, the idea of resting may seem radical. How can we rest when we are surrounded by high achievers and an omnipotent compulsion to stand out? The prevailing mindset suggests that we can always do better, work harder, sleep less, and produce more. It is a toxic narrative that could have only proliferated in a system that values production and profit over everything.

Sometimes, this pressure to self-exploit penetrates deep, even changing our bodies and gradually wearing us down. We have all seen it: at the beginning of each semester, our classmates who initially appear energized and excited, as the semester develops, suffer a gradual physical deterioration as a product of the excess of work and lack of rest they are receiving. As soon as my first midterm comes, bags under my eyes appear, and stress-induced headaches, pale skin, and stomach issues also arise during term season. As finals approach, a friend, who at the start of the semester was the picture of vitality, ends up looking like a ghost with stress-induced migraines and an addiction to coffee. These physical manifestations serve as a tangible reminder of the real cost of perpetual productivity.

This pressure to self-exploit is very present on our campus. After finishing finals and long days of unstoppable studying, I always try to take a break. But I am soon overwhelmed by the feeling that I am wasting my time, and that I should be doing something. As a result, breaks do not really offer an opportunity to rest for me, since they are always accompanied by a feeling of guilt and tension. I am not the only one: for many, every break is a spiral of anxiety where the need for rest clashes with the pervasive guilt for doing nothing. Yes, we feel guilty for resting. The essential act of resting becomes tainted with guilt provoked by a culture that glorifies overworking as a way of sustaining our current economic system.

We have normalized a toxic culture of overworking—in fact, at Harvard, it’s often seen as something to be proud of. This normalization is especially true at this school, we can see it in the all-nighter culture. Libraries are the most alive at 2 a.m., full of students trying to get work done while falling into chronic sleep deprivation. Anyone who has ever been to Lamont at this time can attest. Pulling all-nighters multiple times over the semester is not healthy, and it should not be praised or normalized.

All of this systematic pressure ultimately leads to self-alienation. It divorces individuals from their intrinsic well-being, pushing them into a cycle where productivity reigns supreme. We must resist it, to get out of this cycle we have to prioritize our mental and physical well-being over being productive. In simple words, we have the right to laziness and we must defend it.

So, when your body demands rest, fulfill its demand without hesitation, let it rest, and enjoy. Make an effort to reject the guilt that this toxic overworking culture attaches to leisure. Acknowledge your right to do nothing as an important part of a fulfilling existence. Resist the pressure to view leisure as unproductive and instead, view it as essential for a healthy life. Challenge the prevailing expectations, in hopes of building a culture with a healthier approach to life, both within Harvard and also in our societies. By defending our right to physical and mental rest, we fight for a system in which well-being triumphs over the culture of self-exploitation, and where ultimately life triumphs over profit.

Frida López ’27 (fridalopezbravo@college.harvard.edu) is trying to get at least 8 hours of sleep everyday.