Harvard Art Museums Lecture by Mel Bochner.

The Harvard Art Museums host a variety of events and exhibits open to interested participants of any kind. While the experience of traversing the museum individually and discovering art and new truths on one’s own is not to be undermined, one is also encouraged to compliment this process of growth with the narratives of distinguished individuals willing to share.

One such of these distinguished individuals is Mel Bochner. His lecture given on Wednesday evening at 5:30pm in Menschel Hall discussed the phenomenon in which language has become not a peripheral part of art, but an integral one. The audience was comprised largely of art enthusiasts associated with the University in one way or another. The undergraduates in the room were easy to determine by the lugging of backpacks and the general post-section look of defeat. Regardless of the background of each audience member, everyone had to walk through the cavernous Fogg lobby, down the gray slate stairs, past the flying books, and find a seat in bright orange chairs that put the greens and blues of the Science Center to shame.

The annual Henri Zerner Lecture was introduced by Professor David Roxburgh of the History of Art and Architecture department and Professor Jennifer Roberts of the Humanities. After thanking the Museum, the departments, and the benefactors who make the lecture possible in honor of Professor Henri Zerner, the introductory speeches gave an overview of Bochner’s journey as an artist. Trained at Carnegie, and with a brief stint at Northwestern, he went on to develop his new style in New York. Roberts remarked that Bochner’s interesting relationship with words would certainly lead to an unorthodox lecture.

When Bochner followed with, “I have nothing to add,” he proved that she spoke true. Mel Bochner may be described as a founder of conceptual art, but he made it clear early on in his lecture that he did not consider himself a conceptual artist. Rather, he has simply found new mediums for new ideas he has had throughout his career. Bochner has created photographs of binders, room dimensions, diagrams, and more.

The focus of this lecture and his more recent work has been words; words in their aesthetic appeal, in their physical visual power, and words in their subjectivity and the process of constant redefinition. For Bochner, “The thesaurus captures role of language better than the dictionary.” As he continued in his slow and unassuming tone, Bochner drew attention to portraiture. Photos of words written on graph paper in different shapes are portraits. Bochner stated, “Portraiture boils down to what constitutes representation.” Therefore, for the different subjects of his portraiture he chose a different focus word – followed by all the synonyms of it – organized in a shape significant for the subject. For his own self-portrait, Bochner found himself placing the words “SOUL SYMBOL” and “SPIRIT MIRROR” opposite each other.

These words and others that he found as he “wandered through the landscape of words,” led him to the conclusion that the use of words is constantly changing. After leaving his college thesaurus behind and having to purchase a new one, he discovered that, “Something had reshaped the boundaries of acceptable public discourse.” To what he is referring, is the inclusion of obscenities in the modern thesaurus – which school children use often. His process for using the thesaurus, unlike that of a high schooler trying to beef up a paper, is “like going fishing.” Sometimes you catch something, sometimes you don’t.

Once Bochner has caught his words, he turns towards the colors. The specific color each letter and word is painted in is of deep significance to Bochner. Every letter is painted by hand, though he chooses the colors through improvisation. The visual antagonism that results from this process forces viewers to ask themselves questions about the art: “Is it possible to look at the painting and read the text at the same time?” The art cannot be painting and text all at once, is it only one or the other?

These questions and Bochner’s detailed description of the unique physical process of painting on velvet, lead viewers to believe that Bochner is deeply interested in the medium and the process of his painting. To him, the process is ongoing and subjective. He admits that he will never be able to hear the voice in which any given viewer reads his paintings. The concept of “reading paintings” is one that turns generic understandings of art on its head and forces all those involved to hold every word, color and shape with the weight that it carries.

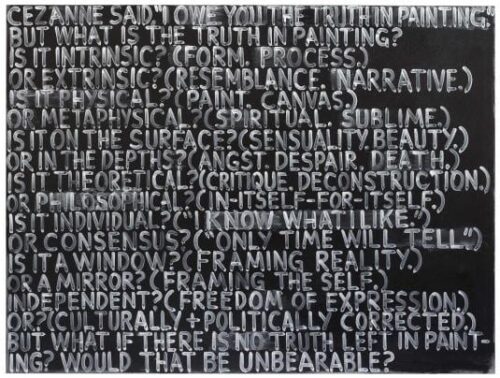

Thus the most poignant and closing moment of the evening came when Bochner read to the audience his painting: Cezanne Said. In a moment of ethereal and powerful author/painter – viewer/reader communion, we all became a part of this process of art and discovery.

Caroline Cronin (ccronin01@college.harvard.edu) wants to find her soul symbol in a spirit mirror.