The Harvard Art Museums—comprising the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Sackler museums—are one of Harvard University’s great prides, housed under the same glorious glass pyramidal roof at 32 Quincy Street. After a two year hiatus, the Harvard Art Museums are back in business.

In their second exhibit since reopening, the museums featured Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives: Creative Communities and White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph. The Independent was given a chance to experience the exhibits with their respective curators.

Prints From the Brandywine Workshop and Archives

The Brandywine Workshop and Archives is a Philadelphia-based institution that creates opportunities for artists who are underrepresented in the mainstream marketplace and conventional museums. Curators Elizabeth Rudy, the Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, and Sarah Kianovsky, the Curator of the Collection for Division of Modern and Contemporary Art, walked us through the exhibit.

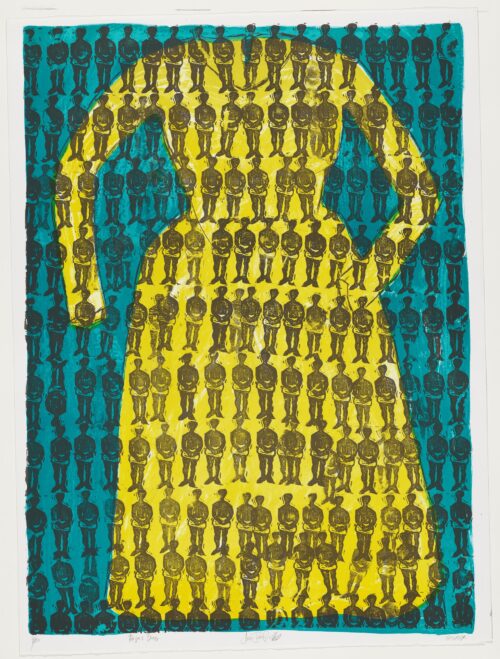

The collection provides a holistic portrayal of Brandywine’s history, with works from the early 1970s to today. The curators selected a wide range of prints, from individual pieces to large multipart installations. The artworks incorporate a similarly broad variety of styles and themes. Cut by Odili Donald Odita features a large colorful lithograph on white woven paper. Janet Taylor Prickett’s Hagar’s Dress, presents a dress as a visual metaphor for Black women and the containers that held enslaved Africans. Women Bring the People by Clarissa Sligh presents a collage of a naked woman with “Women Bring the People who build. Nationals rise and fall” written repeatedly. In this piece, Sligh alludes to the unseen labor of bearing a child.

The Brandywine exhibit adds new meaning to the Harvard Art Museums’ mission of collaborative art with student participation. Rather than providing their own description for each work, the curators invited Harvard students to contribute their own interpretations. Each artwork is accompanied by a written response from a student participant. While some focus on subject matter or technique, others concentrate on the historical perspective. “Their responses have been ever more rich and varied than we’d hoped for,” says Kianovsky.

According to Rudy, the twenty-six different interpretations provide “twenty-six different ways of looking at these prints, which was really our hope from the outset.” She adds, “The hope is that as the visitors go through and read each of these labels, there’s a different kind of engagement with the print medium through each interpretation.

One of the most collaborative works is a multipart installation of black and white portraits by Sedrick Huckaby. Each lithograph is marked with a corresponding name or number. This compilation of drawings was organized by Harvard students in a way they saw fit.

White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph

In the next room, the curators transported us to a different world. What at first appeared to be black-and-white photographs turned out to be far more abstract upon further investigation. However, they maintained distinct photographic elements. It was an exhibit of photograms, photographic images made without a camera.

This exhibit explores the work of Anneleise Hager, a German artist who primarily made photograms from the 1930s to the 1960s. Working in the context of Nazi censure and the dominance of male artists and painters, Hager was marginalized, understudied, and essentially written out of art history. Nevertheless, she remained a remarkably active artist and produced an impressive array of works, all of which the Harvard Art Museums recently acquired and which Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, presented to us.

The exhibit starts with a video explaining what a photogram actually is: a photograph made by placing objects over a light-sensitive surface and then exposing it to light. As a result, the exposed areas darken while the covered areas remain white, hence the name “White Shadows,” coined originally by Hager for her book. Roth described how she saw this title as a metaphor for “thinking about taking that which has actually been obscured and literally showing how bright it is.” The museum is doing exactly that by placing “the spotlight on artists who we haven’t paid attention to in the history of art.”

Hager could do very limited exhibiting during Nazi rule and all of her early work was destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945. However, she embraced her medium despite receiving little recognition and facing substantial obstacles. Although Hager was influenced by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Christian Schad, and Man Ray, pioneers of the photogram, she was experimental in her own right. A highlight of the exhibit is an untitled portrait that presents an innovative combination of a photogram and a photograph.

Prior to being included in an exhibition at Harvard in 2018, Hager’s work had not been exhibited anywhere since 1988. White Shadows is a unique opportunity to experience art that has been largely ignored, a neglect that stems in part, according to Roth, from the view that when “men made photograms they were considered to be artworks and when women made them they were considered to be amateur works or fun pastimes.” This exhibit also celebrates work by other relatively unknown female artists, deliberately and successfully flipping the script.

Together, Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives and White Shadows highlight masterpieces by neglected artists. They are on display until July 31st.

Ariel Beck ’25 (arielbeck@college.harvard.edu) and Andrew Spielmann ’25 (andrewspielmann@college.harvard.edu) wish they were half as talented as these artists.