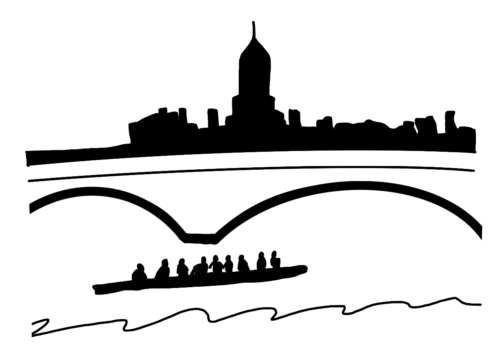

On the penultimate weekend of October in Cambridge, the air was thick with a competitive buzz, food vendors lined the Charles River, and rowing enthusiasts decked out in Vineyard Vines cheered boisterously. These unmistakable signs mean only one thing: the annual Head of the Charles Regatta (HOCR) has arrived. This Sunday marked the end of the 59th HOCR, the largest 3-day rowing event in the world. The Regatta took place from Oct. 18 to Oct. 20, featuring 11,500 athletes and an additional 400,000 spectators. The HOCR course spans three miles and features six bridges, making it a technically challenging race for the rowers and an exhilarating spectacle for those watching.

The race itself stands as a testament to the intergenerational appeal of rowing. Events at the Head of the Charles range all the way from nail-biting races between high schoolers to equally thrilling veteran races, which in the past have featured athletes as old as 91 years of age. This variety means that any two races you watch will always be different, ensuring that the Regatta remains a highly anticipated annual athletic event for many. The quintessential backdrop of vibrant New England foliage further enhances the race’s allure for both spectators and competitors.

Particularly, the Regatta is cherished by Harvard students, spectators, and rowers alike, who are immersed in a thrilling showcase of talent right on their doorstep. Beyond the scope of Cambridge, however, the Head of the Charles also holds great significance internationally. This year’s HOCR featured athletes from 26 countries, including Sam Woodgate ’28, a rower in Harvard’s heavyweight freshman eight from New Zealand.

For Woodgate, the HOCR offers a rowing experience unlike others he has encountered back home or at other global competitions. ‘‘That’s sort of what makes the Head of the Charles such an interesting race. It’s just the turns, the course, and the way that we have to overtake boats in order to get a better time. You set off in 30-second intervals, so you’ve got to be careful where you pass and overtake people. At Weeks Bridge, you’re rowing and you’re drifting around a corner, so you have no sense of boat feel. The boat is really heavy and that’s what makes the Head of the Charles so unique compared to other races.’’

Freshman Ryan Brewington ’28, a rower for Harvard’s lightweight club fours, expressed similar sentiments, considering the Head of the Charles to be a distinctively unique race. Furthermore, the HOCR as a ‘‘head race’’ lends itself to challenges, further enhanced by the tricky bends of the Charles River. These types of races are a category of regatta where, instead of boats starting at the same time and racing alongside each other throughout the race, boats are set off at slightly staggered intervals, requiring faster boats to overtake others at various points along the river, all whilst navigating challenging bridges and turns.

Brewington spoke specifically to the challenges involved in rowing a head race. ‘‘Not having competitors directly by your side, it just makes it a little bit more of a mental game. I think personally, you have to sort of pace yourself, and you have to know if you’re falling off the pace by the stroke coach that’s on the boat. It’s more of a mental race than a physical one because the opponents aren’t directly next to you.’’ As Brewington suggested, the difficulty of the HOCR is only enhanced by the mental pressure of direct side-by-side competition.

Brewington went on to describe specific challenges unique to the Head of the Charles, encompassing both its terrain and format. ‘‘The Elliot Bridge is by far the most challenging part of the course for the coxswains especially. It can be a make or break point of the race for most crews just because it’s such a big turn. You’ll have people getting caught under the bridge, or people trying to enter the bridge with you if you’ve caught up to them or if they’ve caught up to you. It can just be a mess under Elliot Bridge.’’

Despite the challenges articulated by both rowers, their teams delivered strong performances. Brewington’s boat came 13th out of 42 boats in the Men’s Club Fours division. Woodgate’s boat finished 15th out of 30 boats in the Men’s Championship Eights division, finishing with a faster time than the Harvard junior varsity boat, despite the fact he claimed that ‘‘nobody’s really got any expectations’’ prior to the Regatta. Overall these were very impressive debut performances from both freshman rowers.

Coupled with the excitement of the rowers, the energy of the crowd was certainly palpable. Facilitated by the home-river advantage, Crimson spirit permeated the atmosphere, and swarms of Harvard students and alumni were clearly visible along all six bridges and concentrated around the various boathouses. In addition to the multitude of people supporting them, perhaps Harvard’s rowers were also spurred on by a larger ambiance of excitement in the area, as many spectators enjoyed cooled beverages from the FALS bar by the finish line and sported HOCR merchandise. Harvard’s notable performances include a third straight win in the Men’s Lightweight Eight and a second place overall in the Men’s Championship Eight.

All in all, the 59th Head of the Charles Regatta was a smashing success, with an impressive display of exceptional athletic performances and vibrant community spirit, which has further cemented the status of the HOCR as a beloved autumn tradition in Cambridge.

Will Grayken ’28 (wgrayken@college.harvard.edu) has never been in a rowing boat before.