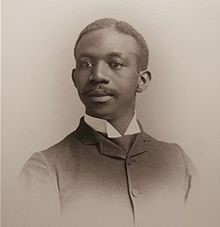

Richard T. Greener ’1870—the first Black student to graduate from Harvard College. George L. Ruffin ’1869—the first Black student to graduate from Harvard Law School. However, Clemont Morgan was the first Black student to graduate from both Harvard College in 1890 and Harvard Law School in 1893. After graduating, Morgan helped found the NAACP and became the first Black member of the Cambridge Council.

132 years later, his great nephew Dr. James Spencer and researcher Leslie Brunetta uncovered an injustice from his tenure at Harvard. While researching for the Cambridge Black History Project, the pair uncovered a research paper detailing how Morgan was denied the right to speak at his Harvard College commencement simply due to the color of his skin. After recently publishing an article on the topic in “Cambridge Day,” Dr. Spencer and Brunetta joined the Harvard Independent to elaborate more on the impacts of the University’s decision, Morgan’s legacy, and how Harvard should retribute today.

In 1890, as Harvard prepared for the commencement ceremony, 44 applicants applied for one of six speakers slots at the event. A panel of professors evaluated each applicant and ranked W.E.B. Du Bois as the best speaker. They also selected Morgan, by a slim majority. However, after significant pushback from panel member Professor Francis G. Peabody, who worried about having two Black speakers, the panel reversed the decision. After internal deliberation, the finalized list was published, with Morgan’s name conveniently left off.

“They told him that he was not one of the six [commencement speakers], when, in fact, he had earned his rights,” Dr. Spencer argued. “What a wasted opportunity to put America, to put Harvard, to put our culture, on the right track—to take us away from the division we’re still feeling today,” he said.

Dr. Spencer believes Morgan and Du Bois jointly speaking could have set a powerful precedent. “All of these people who came down the [graduation] line at Harvard wouldn’t have been able to say, ‘Well, we’ve never seen Black intelligence rise to the top.’” he said.

“There was just very prevalent belief among the white population—most of the white population—that no matter what Black people actually demonstrated, they were not intellectually up to white people,” Brunetta added, alluding to how many individuals at the time were embarrassed to acknowledge Black prowess—this denied speech a clear instance of such fears.

However, more importantly, Brunetta and Dr. Spencer argued that the University was facetious about the selection of the commencement speakers. “They lied. They lied to my uncle,” said Dr. Spencer.

“They lied to everyone else because they said, ‘here are the six.’ Du Bois is one of them, but there should have been Du Bois and Morgan in that group. And they basically pitted them against each other. I mean, unknowingly, the two of them had no idea this was going on,” concurred Brunetta.

According to Brunetta, Morgan’s situation was not a unique event. There have been multiple instances of Harvard hindering away Black Excellence. For instance, Professor Josiah Parsons Cooke’s Black research assistant, Francis Prince Clary, was written out of Harvard history. Despite helping to discover “a systematic approach to understanding matter,” Harvard mislabeled him. “[Harvard said] he’s just a janitor, even though he’s the right hand man [to Cooke] and assisting in every chemistry demonstration for decades,” said Brunetta.

As part of their work with CBHP and Cambridge Day, Brunetta and Dr. Spencer are working to uncover more of these stories. Finding these pieces of history is a critical process for Brunetta and Dr. Spencer that they referred to as “Unhiding.”

In addition to their mission to raise awareness about important historic Black contributions at Harvard, Dr. Spencer also believes the University hasn’t done enough to compensate for their past injustices. “I’ve never seen remorse from Harvard,” he said. “I wish I believed in Harvard enough to think that they would do anything [to make up for their past]—you haven’t done much for African Americans.”

Beyond just making up for past mistakes, Dr. Spencer also commented on Harvard’s present discriminatory real estate practices, as the University has purchased much of the housing in Cambridge which includes formerly Black-owned apartment complexes. “Harvard pretty much bought up all the houses of the African American community. If you go walk down Memorial Drive, going towards Western Ave, and you see those buildings, a lot of those buildings used to be Black-owned,” Dr. Spencer continued.

As Black residents continue to be pushed out of the community, Dr. Spencer worries one day that Black people will no longer call Cambridge home. “We might not be here in 20, 30 years. And so I want the story to say, ‘Hey, you know what? We were once here, and we once contributed mightily to the city.’” This mission has fueled Dr. Spencer’s involvement in the CBHP, which aims to maintain Black history as an integral part of the Cambridge community’s development.

Dr. Spencer felt personally impacted by the decision to cut Morgan’s graduation speech, or as Dr. Spencer refers to him, “Uncle Clem.” To Dr. Spencer, the future of African American history at Harvard is important, and he believes the University should work harder to uplift the population they have continuously wronged.

“I think Harvard owes it to African Americans, based on, in part, what they did to my uncle, to bring in more African Americans,” Dr. Spencer commented.

Kalvin Frank ’28 (kfrank@college.harvard.edu) recommends anyone interested in the Black history of Harvard connect with the Cambridge Black History Project.