In an inconspicuous building on 32 Quincy Street lies the University’s hidden gem: the Harvard Art Museums. Simply walking into the building is an enchanting experience—the courtyard itself is a work of art. But walking through the museum is an enriching engagement with some of the most important artists and works of art history canon.

The Harvard Art Museums are composed of the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum. The three are all contained in one building, though each individual museum retains its original focus. Established in 1895, the Fogg is the oldest of the museums and renowned for its incredible collection of Western art, stretching over three out of the five levels of the museum complex. Here are some of its highlights, from Dutch Age masterpieces to American contemporaries.

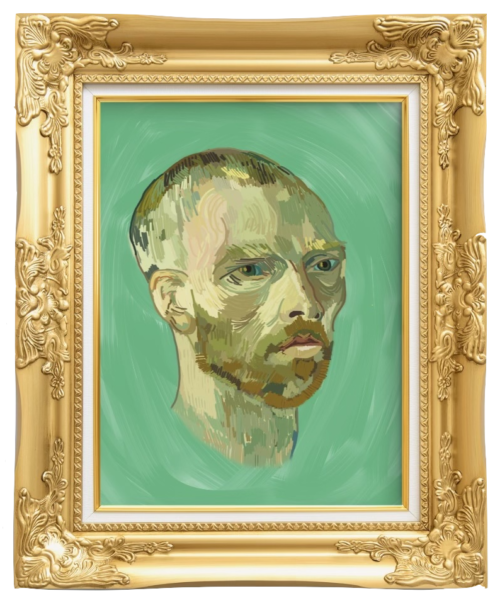

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gaughin (1888) [Level 1, Room 1220]: Located in the Maurice Wertheim room on the first level, Van Gogh’s self-portrait is immediately eye-catching due to its luminescent veronese green background and thick brush strokes. The inscription, “To my friend Paul Gaughin,” is only faintly visible at the top of the painting. Van Gogh initially sent the painting to him, spurring a brief portrait exchange between the two. However, shortly after sending the portrait to Gaughin, their friendship abruptly ended. Around fifty years later, the painting was seized by the Nazis.

Claude Monet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train (1887) [Level 1, Room 1220]: A few paintings to the right of Van Gogh’s self portrait, this work is Monet’s largest piece from his famous 12-part series of the Saint-Lazare station. Pieces from the series are scattered worldwide, each presenting a slightly different perspective of the station. His use of impasto, the thick application of paint so that it stands out from the canvas, for the smoke illuminates the effects of rapid industrialization in Paris. Monet is famous for painting nature but notably did so when industrialization was engulfing Europe. Just upstairs, for example, his Charing Cross Bridge: Fog on the Thames (1903) presents an even more whimsical and impressionistic view of a city tainted by industrial pollution. Arrival of a Train sits among other 19th and 20th-century artworks that depict new scenes of modern, urban life in the Wertheim room.

Nina Chanel Abney’s Four Stops (2007) [Level 1, Room 1330]: Only recently put on display, Four Stops is an enormous contemporary work that depicts a surrealistic ride on the subway. The work is composed of abstracted and distorted figures, bold and contrasting colors, and incredible amounts of expression. Abney uses surrealism to evoke alienation and a lack of human connection between commuters.

Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (2008) [Level 1, Room 1200]: Across the museum, Marshall’s Untitled is a powerful work. In this work, a Black painter assertively stares at the viewer while dipping his paintbrush into black paint on a grand palette. This piece directly responds to Langston Hughes’ 1926 essay encouraging Black artists to embrace Black culture.

Peter Paul Rubens’ Neptune Calming the Tempest (“Quos Ego”) (1635) [Level 2, Room 2300]: The second floor of the museum dynamically moves back in time and across the world. Rubens’ small work is hidden in the corner with other Dutch and Flemish Art. The oil sketch, based on a passage in Virgil’s Aeneid, illustrates a majestic scene of Neptune protecting Aeneas’s fleet to commemorate Cardinal Ferdinand’s safe arrival in Antwerp in 1635.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Raphael and La Fornarina (1814) [Level 2, Room 2200]: Ingres’ depiction of the master Raphel’s sensual relationship with his mistress is a painting about painting itself. While the mistress sits desirably on Raphel’s lap, he stares out lovingly toward his own work of art—a portrait of her—instead. The mistress gazes at the viewer directly, as does the portrait. She resembles the depiction of the Virgin Mary hidden in the back of the painting, as well as the subject of Ingres’s famous Grande Odalisque (1814).

Jacques-Louis David’s Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (1817) [Level 2, Room 2200]: Right across the room from Raphael and La Fornarina radiates David’s neoclassical portrait of Sieyès, a French Revolutionary leader. A member of the clergy, Sieyès is famous for writing the pamphlet “What is the Third Estate?” that served as a rallying cry for the National Assembly, formed by the Third Estate in 1789 to draft a new constitution. Both the artist and the subject uniquely survived decades of political turmoil from the revolution to the reign of terror and its aftermath.

Albert Bierstadt’s Rocky Mountains, “Lander’s Peak” (1863) [Level 2, Room 2100]: Nestled in the other corner room with Monet and Sargent, Bierstadt’s work offers an American angle on the 19th century in contrast to the European paintings we have encountered so far. His grand landscape painting is based on sketches he made during a U.S. government survey expedition in 1859. He presents an ethereal view of nature interacting with light. However, the Eastern Shoshone people, who had inhabited the mountain range for thousands of years, are absent from the work. In portraying a heavenly landscape, this painting matched the ideal of Manifest Destiny, which encouraged westward expansion.

The museum’s third floor is adorned with marble sculptures and pottery from Greek and Roman antiquity. On its other side lie the Special Exhibitions Gallery and University Galleries. It is here, I find, that you grasp the best view of the courtyard—the first and last artwork you encounter.

The courtyard is an affair of dynamic light and a flawless blend of contemporary and classical. The two-story arches model the facade of the San Biagio complex in Montepulciano, Italy, in a timeless Renaissance style. The walls then seamlessly meet glass that stretches to a truncated, pyramidal roof that ushers in natural light into all five floors. Works peek out from the row of arches that enclose the airy courtyard. Looking up, the installation Triangle Constellation (2015) by Amorales floats in the air, a sculpture composed of 16 musical triangles. It creates a visual, and physical once played, collective experience of sound that reverberates through the galleries. The courtyard is a dynamic and radiant space that serves as the perfect beginning and end for the visitor’s experience at the Harvard Art Museums.

These pieces are a mere few of the Fogg’s highlights—the rest are waiting to be explored.

The Harvard Art Museums are free to all visitors and open 10am-5pm, Tuesday through Sunday.

Meena Behringer ’27 (meenabehringer@college.harvard.edu) loves to get lost in the Fogg.