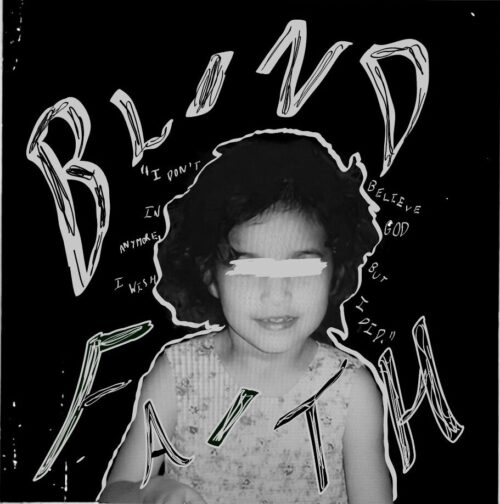

“Oh, I don’t believe in God anymore.”

“That makes sense.”

Suddenly, the size of my left wrist became more interesting than our conversation. I gripped it in a chokehold for a few moments.

“What?”

My eyes didn’t leave my hand.

“But, I wish I did.”

I drew in a sharp inhale. The words left a bitter taste in my mouth like I had just squashed a bug on my tongue and swallowed. My therapist waited for my eyes to meet hers, letting the ticking of the clock grow louder. For me, having patience and being silent were both like holding my breath. I could only last for a few moments. I looked up, knowing what she’d ask.

“Why is that so bad?”

I shrugged, wondering the same damn thing even though it felt so obvious.

“If you could guess.“

***

My eyes flickered anxiously to my father. He reassured me with nods as his mother dug through her purse for her “gift.” He could only last a few moments before he snatched the purse and pulled out a sharp steel band, holding it up to the hot Orange County sun. I recognized this gleaming never-ending loop. Everyone in their family wore one except for me, the youngest daughter. While I knew it as the “weapon” that always cut me, their family knew it as the kara—the steel band, recognized in all religions, representing one’s ever-lasting, unbreakable bond with God.

“Put it on! Put it on her!”

I looked over at my quiet mother. She had her arms crossed against her chest. It was the first time I noticed how bare her wrists were. I didn’t realize my grandmother’s raising my hand until I felt the cold steel touching the top of my fingers. I flinched, and immediately, her grin melted into a disappointed frown.

“Put it on.”

My father gave me a look—never with me—and easily slid the kara onto my wrist. I tugged and squeezed, believing if anyone could bend this metal, it’d be me. My father quickly shut me down, taking my wrist away.

“Never take this off.”

“What if I want to?”

He laughed as if what I asked was ridiculous.

“My wrist will grow.”

“Bigger than this?”

He raised the band, my dead arm rising with it. That was a lot of empty space.

“What about her?”

I searched for my mother as I whined, but she was already disappearing indoors.

“Listen to me.”

My father’s command hung in the dry air as I stared into the house. Where did she go? He turned my chin towards him, and my eyes fixed themselves on the steel band.

“You won’t take this off.”

I nodded, snapping my head back to the house. I was determined to find her now, but my father had other plans. He held onto the kara, pulling me back and lifting me to the sky. He’d spin me around, throw me into the air, and catch me with his calloused hands. He’d wrestle me to the ground and let out bellowing laughter as I, at the age of six, attempted to fight back against his sturdy six-foot-four frame. Despite knowing I’d never win, I played his game, for I liked how he took up so much room, how real he felt. Yet, while I grew, he never made space for me to breathe. Soon, his pulls on my wrist left me red and raw, his laughs turned into flinching roars, and his playful wrestles became wheezing fights for life. I realized I might never outgrow his twenty-four-hour games, for there was no one else who sounded or felt like him.

***

“I only believed in God out of necessity. When you can’t see hope, you have to create it, right?”

She furrows her brows at me for a moment; something about what I said, or what she expected me to say, was off. I press instead of changing directions.

“I mean how else was I supposed to survive?”

“No, no, that makes sense. It’s very common. When did you stop?”

“When he was gone.”

“Your father or God?”

“My father. I try not to see God as a he anymore.”

She raises her eyebrows at this, understanding now what wasn’t sitting well. A few moments pass as I wait for her to ask what I’m already supposed to know.

“Did you ever?”

***

“He’s not coming back.”

Her commanding whisper led to the flood of my sisters’ cries. I kept my dry eyes on the edge of our coffee table. In a moment, the door slammed shut, hushing all noise behind the connecting walls. I loosened my grip of the table to give my now-bent, bare wrists a break and turned to my right.

The afternoon sun cast a dull pale light over her. She wore a college sweatshirt and old yoga pants. She had high cheekbones and straight blonde hair that framed her square jaw. She was young. There were dark circles underneath her green eyes. I looked at her for the first time as my mother, the woman who eluded him with silence. She was the one to whom I had given my blind faith. There was no tenderness between us, mother and daughter. We were far too tired, weary, and hardened for intimacy. We shared no words. Yet, just from the sight of her, I believed she was real, grounded. As her presence settled over me, so did my disbelief in God.

When I took a breath, she left. I was alone now in our apartment’s silent living room. For the first time, my feet sunk into the floor and my shoulders drooped. I stared out of the living room window, looking for nothing, and I liked how quiet it was, how much space I filled.

“I’ve never experienced that feeling again. Not even come close.”

“But you don’t believe in God anymore, so—”

“I know. Maybe I made the wrong decision.”

“A bit harsh to judge the decisions your ten-year-old self made.”

“Maybe I should believe again.”

She’s not convinced.

“Why is faith in God the solution?”

***

Even in a new home, my city’s early morning light still brought the same image: my mother eating dry cereal at the kitchen counter, basked in that soft yellow glow. She and I always woke up early, bursting out of bed, in an excited relief to leave the dark. This was my first morning back for winter break.

I slid into the living room, peeking into the kitchen. The comfort of consistency suddenly vanished as I turned to my right and saw her in the midst of a prayer. Her eyes were closed, surrounded by the smoke from the lit incense. I barely processed the image before my mouth interrupted the silence.

“What the hell are you doing?”

Her eyes snapped open. She glared at me but wouldn’t dare to respond. Her words with God weren’t finished yet. I turned my back to her, waiting for the ring of a bell. The sound conjured memories of my grandmother. She always caught me watching her as the sun rose. Her hums and bounces and bells entranced me. Entering her room of prayer, I listened to her stories about sacrifice: what do you love so much, you’d kill it to save the sun, the world? At first, the stories brought fear, but slowly, I desired to be the bravest, the most willing, the most loved.

After she finished, I opened my mouth to apologize, knowing my gut reaction was something I still had to train, but she was ready for it.

“Don’t insult my God.”

Her growl was laced with fear as if she had psyched herself out from rehearsing too often. A smirk creeped onto my lips, but I caught it before it showed: there was no need to push on pressure points. She continued.

“He’s the reason we’re here. He saved–“

My face scrunched up into a mixture of disgust and anger. I laughed.

“Your God never did anything for you. You’re the reason we’re here.”

As a child, I prayed and believed in her, that one day she’d run off with me and my sisters to the rising sun. We would leave the night forever, and she would know of the sacrifice I had no choice but to make: silence. As a child, I believed she was perfect, so she saw me and she heard me and she knew.

Three years later, I realized I was slowly choking, as if I had survived drowning in an ocean only to die from the puddle left in my lungs. I stood under a dull, fluorescent light in a gray, darkening stairwell. I had asked for privacy as I was far too embarrassed not knowing how I would react once I spoke. We were on the phone together. She would have to hear me as I could never look her in the eyes and actually speak, not create noise to keep the peace, but cut through the air with revelations.

I took a breath and told my mother what he did to me. After, I immediately dropped to the ground to catch my breath, my aching lungs almost empty at last. She waited until my mind settled, so I remembered her presence.

“Are you sure?”

It took me several moments to process her question, to understand she didn’t know. While I said the truth as a revelation, I hoped it’d be noise. I hoped I could hear, even create, the lie from her response. I had prepared myself to fight, to ensure she couldn’t deny the truth. But, this question did not even reveal an ignorant turning of the eye. She was always prepared; she could not lie, or veer away from her gut, in a state of shock. She never heard or saw or knew. Instead, my mother had thrown her blind faith into my silence, my grins as my father spun me around in the air. The “sacrifice” I made had always been a manipulation tactic, his weapon against me, but I knew this. I just could not feel it was true, that what I kept secret was never for the “greater good” of my sisters and mother; rather, it was to protect him.

What filled me then was far worse than water: rage, hot and red anger with no one, nowhere, to take it. This balloon sitting at the bottom of my stomach had been inflating since I was a child, so I desperately wanted to forgive, to pop this tumor-like ball my past lived in, but did I have anyone to blame? My father was a ghost of the past, the thing that I forgot was still living. My mother, though, was here, but up until this moment, I had made the mistake of believing she was perfect, all-knowing. Would forgiveness even change anything for me?

***

“It’s a lot easier to be angry at God than at him or her or anyone really.”

“You want closure.”

I opened my mouth to react, but I didn’t need to continue. She had caught up to me. She gave me a weak smile, recognizing the growing pains of becoming a woman who wanted to take control of her own story. That in order for me to do so, I had to grieve instead of forgive. I had to believe in the only one who knew me, who I couldn’t tune out or turn away from, who could simultaneously be imperfect and all-knowing. Instead of throwing blindly, I had to willingly place my faith in me.

I returned the weak smile. The fatigue settled in my body, and I pressed my back against the plush armchair as the ticking clock filled my ears like a slow heartbeat teaching me the rhythm to breathe.

Arsh Dhillon ’23 (asekhon@college.harvard.edu) is the President of the Independent.