Students react to binary survey.

By MEGAN SIMS

Every February, as Cambridge residents bundle up for below-freezing temperatures and feet of snow, Harvard undergraduates await a festive pink and red email in their inbox inviting them to participate in the Harvard Computer Society’s annual Datamatch survey. The survey, which contains a series of increasingly silly questions written by HCS, is intended to match students with others of their preferred gender for a free platonic or romantic food date on Datamatch.

For students who identify as “male” or “female,” especially those who also identify as cisgender and heterosexual, this may accurately reflect the way they approach dating. However, for LGBTQ+ students, especially those who identify as non-binary, Datamatch’s survey distinctly and deliberately leaves no space for them.

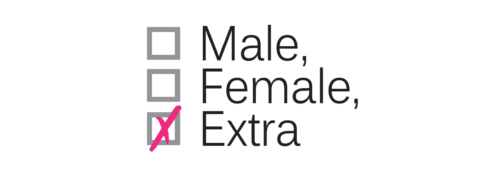

Non-binary is a broad umbrella term for a number of gender identities that do not fit in the traditional male/female binary prescribed by Western culture. Non-binary people may be aligned or feel affiliation with many genders or with none, may take any pronouns, and may be attracted to any number of genders similar or different from themselves. But, in the survey put out by Datamatch, this constellation of gender is completely erased to the point that students who do not identify as strictly male or female have been forced to only specify their real gender in a box labeled “extra.” Datamatch’s algorithms then display this information as “Jane Doe is a Sophomore female (non-binary),” continuing to misgender students and placing them in categories which do not accurately reflect their identity.

This has been Datamatch’s standards for years, but this year students, who have been privately contacting Datamatch about this issue during their full tenure at Harvard, began speaking up publicly. A post in the HCS Datamatch 2017 event by a student poses the question to the creators and organizers that if students do not identify as male or female, should they not participate in Datamatch? Datamatch’s answer, in short: yes.

Datamatch has justified the choice by saying that their algorithm works better with binary pairings, an excuse that seems rather flimsy when the choice is either a bit of extra work for the programmers of the Harvard Computer Society or entirely excluding a portion of Harvard’s populations from using your services. In short, it is choosing the easy, transphobic way out that emphasizes a harmful gender binary over the lived realities of students.

Darius Johnson ’18, who identifies as non-binary and whose poetry is often published in the Indy, participated in Datamatch for the first time this year. When faced with the two reductive gender options on the survey, Johnson said they weren’t surprised. “What I was surprised about,” said Johnson, “was that their solution to incorporate non-binary was to have any extra gender identifying information in the ‘extra’ section of the form.” For them and for many students this sent the message that, in the eyes of HCS, “The binary is normal and anything else is extra information.”

Johnson spoke about their own personal feelings of discomfort with the system. “It was very troubling that these people decided that any identity that was non-binary or not cis was just extra information. It was really unsettling. Being on this campus, there are so many opportunities to learn how to avoid problematic things like that and there are so many people who are trying to educate the campus about non-binary identities, so it was just a blatant disregard for these communities”

Johnson is not alone in these feelings. In our conversation, they told me that the collective frustration surrounding Datamatch has pushed students to have conversations and mobilize around the issue. They said that much of this has occurred over the email list of the Black Students Association. The black queer community has been leading the fight over this issue.

According to Johnson, “[Datamatch’s] reasoning has been completely and utterly unresponsive and inappropriate. And I haven’t really seen an effort on their part to apologize or to say ‘we’re gonna fix it.’” Students continue to push for Datamatch to make these changes and to support students of all gender identities.

Megan Sims (megansims@college.harvard.edu) hopes to see the Harvard Computer Society put their coding skills to work in the future to include multiple gender identities.