If you polled college students, most would claim that their favorite time of year arrives during spring break, the winter holidays, or the last few weeks of school. For me, it’s the day that daylight saving time begins.

Daylight saving time begins in early March when the clocks jump forward an hour and ends in early November when they reset. The practice started in World War II as a strategy to conserve energy and has persisted ever since. Daylight saving time pushes summer sunsets later and keeps winter sunrises early.

The night before the clocks spring forward by one hour, I make sure to be tucked into bed by midnight to secure a full nine hours of sleep. After my usual morning routine of stumbling out of bed in search of a matcha latte, I spend this day reveling in the outdoors as much as possible.

With birds chirping overhead, the soft melody from my headphones filling my ears, and the cool, early-March breeze brushing against my skin, I feel truly content.

Having lived in the Boston area since I was eight, I’ve endured ten winters with sunsets before 4:30 p.m. Each time the clocks roll backward and we lose an hour of sunlight, I genuinely feel that my quality of life declines—not by a large amount, but by a measurable one.

During the late months of high school winters, there were days when I boarded the school bus just after sunrise and returned home long after dark. For an entire week, I never saw the sun above the horizon. Through every Boston winter, days felt longer, productivity became challenging to muster, and feelings of sadness lingered for greater periods. It even feels sad to write this down.

For me, the end of daylight saving time signals the start of what I call “daylight craving time.” If you asked around Harvard’s campus, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who cherishes the hour gained more than I do. Likewise, you’d struggle to find someone more disappointed on the day we lose an hour of afternoon daylight.

And yet, despite my deep disdain for what I consider an unnecessary and utterly contorted practice, I’ve recently concluded that making daylight saving time permanent might not be the best solution.

The term “daylight saving time” suggests that we somehow save more daylight from March to November. Who could argue that more daylight is a bad thing? Now that the sun sets after 7:00 p.m., students can enjoy precious daylight after classes. This means more picnics in Harvard Yard, trips to Newbury Street, and, overall, more good vibes.

Spending more time outdoors offers an array of benefits. Increased outdoor activity is associated with greater levels of physical exercise and lower levels of sedentary behavior, both of which reduce the risk of health issues, from diabetes to cancer and heart disease. It also correlates with improved mental well-being.

In 2022, the United States Senate passed the Sunshine Protection Act, aiming to enshrine daylight saving time permanently year-round. While the bill never made it out of committee in the House, it did raise the question: if daylight saving time encourages individuals to spend more time outside, what could be the harm in making it permanent?

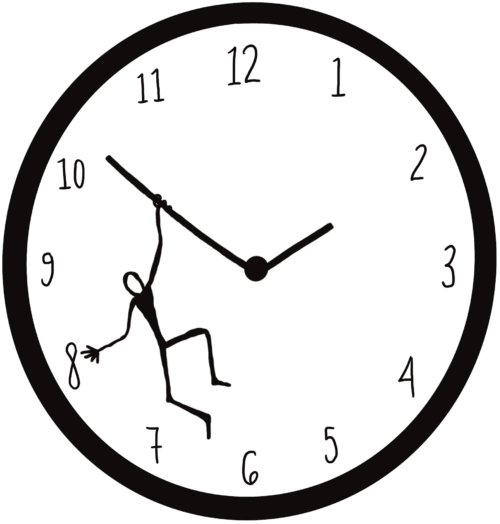

Experts caution, however, that there are many hidden risks in making this switch that might not be immediately obvious. Scientists generally agree that shifting the clocks forward year-round would disrupt our circadian rhythms—our internal 24-hour clocks—aligned with the external day-night cycle. While we would gain an extra hour of afternoon sunlight, the long-term effects on sleep could be detrimental.

Even more startling is the potential link between permanent daylight saving time and higher cancer rates among Americans. Although the research is still ongoing, researchers have found that circadian misalignment could increase the risk of various cancers, including breast and lung. Melatonin, a hormone key for regulating sleep and associated with the circadian rhythm, plays a role in fighting tumors and may be impacted by this disruption.

It may come as a surprise that this information isn’t more well-known. It certainly is to me. However, Harvard’s own Charles Czeisler ’74, a Professor of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School and “Gen-Ed 1038: Sleep” instructor, offers a convincing explanation for the phenomenon in an article in the Harvard Gazette.

“We are affected by light in ways we don’t think about,” he said. “We want to be able to decide when we do things, when we sleep, when we wake. But we are not as far removed from nature as we might like to think.”

In fact, we’ve already attempted to remove ourselves “from nature” before.

In 1974, the United States implemented year-round daylight saving time to reduce energy costs. However, just 10 months later, support for the policy plummeted from 79% to 42% after Americans experienced the dark mornings of early February. The policy was ultimately repealed, and the intended goal of reducing energy consumption was also not achieved. It was a massive failure.

I relish the extra hour of afternoon sunlight that daylight saving time brings in March. It’s no exaggeration to say that it has had a significant positive impact on my life. But as I reflect on it now, I realize that the harms of shifting all the clocks forward—from disruptions to sleep quality and the increased risk of life-threatening diseases—far outweigh the benefits.

In a few months, I’ll once again have to do my best to fight my way through “daylight craving time.” For now, I’ll savor every extra hour of afternoon sunlight I can get until November.

Ishaan Tewari ’28 (itewari@college.harvard.edu) can now be found at the Boston Public Garden at 7:00 p.m.