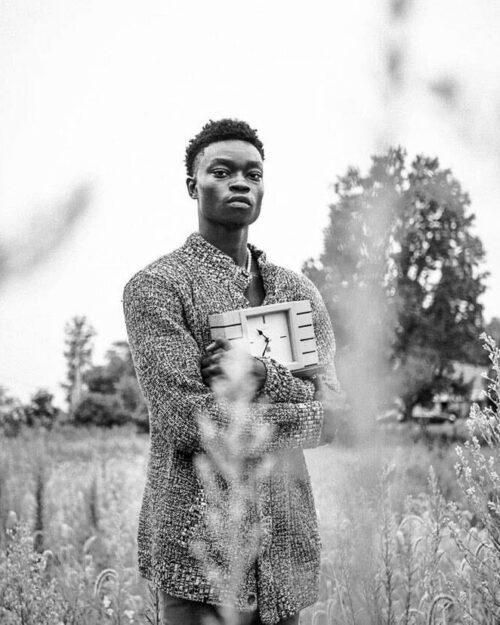

Harvard has a rap scene, and its members are making moves. Student rappers are travelling across the country to record, throwing live shows, and giving back to their communities. The Independent spoke to Jaeschel Acheampong ’24 (“YoungJae”), Erick Silva ’25 (“E Moreland”), and Braden Ellis ’24 (“shock apollo,” recently changed from “brady williams”). Acheampong has released a project and multiple singles, Silva has released four singles, and Ellis is a producer that has put out multiple instrumental projects.

Rap songs are often discussed as a combination of vocals and an instrumental. With regards to vocals, a rapper has to have both lyrics and flow that come together to make a distinguishing sound. These vocals must work in tandem with an instrumental to create a compelling song. Beats can incorporate audio files found online, samples from other media, or recorded loops created by the producer themself or a collaborating artist. For those with a strong musical familiarity, the production of beats is often where songs really reach the next level, particularly when the producer can make many of the instrumental loops themselves. Acheampong and Silva both write their own lyrics and can produce their own beats. Acheampong has a wide variety of musical skills, playing primarily viola, saxophone, and piano. His instrumental skills have enabled his great variety in production and given him a certain musical intuition. “I knew what would sound good,” Acheampong said about first getting into the song-making process.

Silva described how music inspired and shaped his childhood. “I would run through phones listening to so much music,” he said, highlighting the classic enemy of music lovers: their phone’s battery. Recently, he put in serious effort to connect with other producers, taking a weekend of this semester to travel to New York City and Philadelphia to visit different production studios.

Ellis, though not a rapper himself and more partial to neosoul, a unique music style strongly connected to soul and R&B, has produced a number of beats that could be utilized by the rap genre. Years of experience with violin, bass, and other instruments allow him to tap into a wide variety of sounds.

All of the artists highlighted the importance of collaboration in their music. Acheampong emphasized the cross-genre nature of rap. “Something I like about rap music is that it blends a lot of genres,” he said.

The artists also emphasized Harvard’s role in this area. Harvard makes an effort to admit artists from all over the music world, and Acheampong appreciates the accessibility of musicians with different specialties and styles. “I know that because of Harvard, I can reach out to [them],” he said. However, Ellis did make note of the difficulties that come with trying to work with other artists. “Collaboration is something that takes a while to smooth out. People have different schedules and ideas,” he said. For Silva, even the geographic location of Harvard was an advantage. Coming from next-door Somerville, Massachusetts, he already had some awareness of the professional studios available in Cambridge when choosing to attend. “It would be hard to make music if I wasn’t at Harvard,” he said.

Harvard received a less definitive appraisal with regards to its physical resources. While some music production spaces exist on campus, these artists had to bring at least some personal equipment from home. Acheampong recently performed at Black Convocation, a celebration hosted by the Harvard BSA to welcome Black first-year students to a supportive community of other Black students, and was critical of Harvard’s hardware.

“Harvard has very bad speakers and very bad mics. It almost discourages people who want to do that kind of performance,” he said. He wasn’t entirely sure how to appraise Harvard’s resources for actually making music, but he did say that the college has “not the best resources to produce your own music, but the best resources to market your music.” Ellis focused more on the necessity for Harvard to actually provide more production resources. “If you’re trying to rap, you don’t need a studio,” he said. His own beat-making career started with just a computer, earbuds, and a keyboard.

Unfortunately, for a college of young people that grew up during the era of “SoundCloud rappers,” many students do not take the idea of a rap career seriously. Silva commented on light jokes that he’s experienced. “Some people call me Lil Pump,” he said. Ellis identified common misconceptions experienced by rappers and producers:

“There’s these two stigmas when you tell people that you want to make beats or want to be a rapper. Not everybody knows what a producer is. They ask, ‘Oh can you DJ?’ I don’t know how to DJ, but I say yes. For rappers people say, ‘You came to Harvard to do rap?’ The nice thing is that being able to make beats demonstrates that you understand music. But people hear you want to rap and think about SoundCloud rappers. You feel that pressure on you. ‘What do you have to rap about? You go to Harvard!’”

Acheampong explained the skepticism that he often faces when telling peers about his music. “It takes people a second to take it seriously. I let them hear it and then come talk to me about it. They’ll say, ‘Oh, you made this? This is actually good. This is something I’d actually listen to,’” he said. Silva expressed a desire to correct any misconceptions about rappers in the Harvard community. “I want to change the narrative, if there is one at all,” he said. Skilled rappers are talented musicians just like any member of Harvard’s bands and orchestras, and it seems appropriate for them to be respected as such.

It should be acknowledged that being a rapper has also allowed for many positive social experiences for all artists we talked to. Ellis recently made beats on the fly for some friends on the basketball team to freestyle to. Acheampong’s performance at Black Convocation was wholly well-received. Silva is excited for opportunities to create great experiences for his fellow students, even giving the Independent a promise: “I’m going to perform at a Harvard bash.”

Part of being a rapper is deciding what areas your content will cover and how you choose to approach your subject matter. Silva has developed clear standards that he and his friends follow when making music. “I have three rules: don’t talk about guns, don’t talk about drugs, and don’t say anything derogatory towards women.”

Acheampong admitted that he initially slipped into less genuine subject matter when first making music. “One thing that I used to do when I first started to make music is lie. Then one of my friends told me, ‘You have more in your life to talk about.’” Though it may feel easy to slip into what Acheampong calls “rap talk,” he seeks to use honest material in his music.

“I have three rules: don’t talk about guns, don’t talk about drugs, and don’t say anything derogatory towards women.”

-Erick Silva ’25

Silva generally sticks to subject matter that reflects his lived experience. His song “Beat the Odds” reflects on the difficulties faced by members of his community. Honestly representing his experience and his home is important to him. “No matter where I go, where I come from is never going to leave me,” he said.

Silva has already used his music to give back to his community. In August of this year, his first show raised $1600 and 250 pounds of canned goods for the Somerville Homeless Coalition. “I want to help my community out,” he said. He has a simple model that has already started working: “Make good music first, then push social change forward.”

There are currently no official student organizations dedicated to making rap music at Harvard, and it’s unclear whether such a group could materialize. “As of right now, the Harvard I know, there aren’t a lot of people who are into making that kind of music,” Acheampong said. Silva has thought about trying to get a rap club started himself. “People have told me I should start one,” he said.

How do you get started? Silva shared a piece of advice a producer once gave him: “Don’t go away from anybody without letting them know you make music.”

Ellis has some basic recommendations and a friendly offer: “Just start writing and get a flow together. Nobody wants someone with no flow. Come find me. I’ll get you straight.”

And if you know someone who’s trying to enter the rap world, Acheampong encourages you to respect their work. “Support your friends,” he says. “If they’re going to post something, listen to it. If you rock with it, tell your friends about it. Don’t be a bad friend.”

Look out for new projects and singles in the coming months from these rising stars in the Harvard music scene—YoungJae, E Moreland, and shock apollo.

Harry Cotter ’25 (harrycotter@college.harvard.edu) enjoys casually freestyling and not listening to country music.