“Hair Love”

The Independent considers why this Oscar award winner is an important piece of film

By MAYI HUGHES

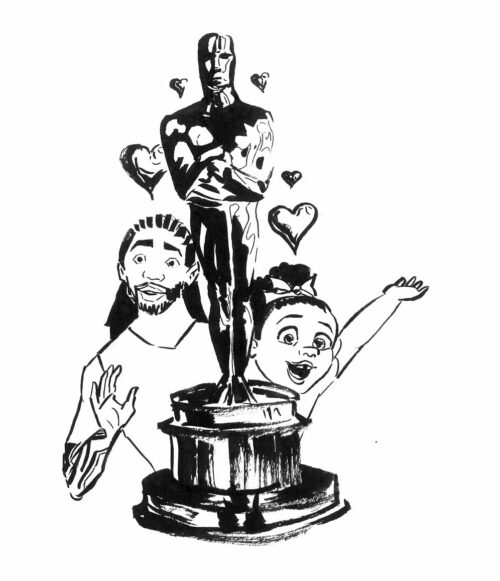

Earlier this month, Matthew Cherry and Karen Rupert Toliver’s ‘Hair Love’ won an Oscar for best-animated short film. The six minute clip tells the tale of a black father learning how to do his daughter’s natural hair for the very first time, while her mother is away at hospital ; the film is funny, sweet and a real tear-jerker. But it’s also so much more than that. It’s a triumphant tribute to black womanhood, black hair and perhaps more importantly – the beauty of father-daughter relationships.

The short film begins with the main character – Zuri- excitedly waking up and rushing to prepare for the day. Bonnet adorned, and wide tooth comb in hand, she approaches the bathroom mirror to tackle her afro. Zuri selects a style from a natural hair channel to copy, and a flashback is shown of her own mother doing that style. Tug by tug, comb by comb, Zuri attempts to moisturise, part and collect her hair into a four knotted style. But to no avail. The frame switches to a her shocked Dad walking into the room to see a disappointed Zuri. The dad, having never done his daughter’s hair before, struggles to style it. After tugging and pulling, he attempts to put a hat over his daughter’s hair, which causes Zuri to run out of the room in tears. The father successfully creates Zuri’s chosen style and they go to visit Zuri’s mother in hospital.

While on stage at the Oscars accepting the award with Rupert Toliver, Cherry remarked: “we wanted to see more representation in animation (and) we wanted to normalize black hair”. Years ago, to think of a good animated film was to think of Disney – the Cinderellas, the Snow Whites, the Sleeping Beauties. Historically, the scope of animated film has been restricted, due to the same, big, white names dominating the industry. There hasn’t always been a space for stories like Cherry’s – for characters like Zuri. When Cherry first began crowdfunding for his film, in the 100 year history of animation, there were only three animated feature films including black protagonists. Cherry’s film is an unapologetic representation of a young black girl in all of her frizzy glory – a long way away from the damsel in distress our screens have grown accustomed to.

Notedly, Cherry shouted out Barbers Hill High School student Deandre Arnold, a student whose school had suspended him due to his dreadlocks going against the district’s dress code. Black hair has always been a tool of expression within black communities. Whether it’s dreads, or braids or the natural afro, hair has been an act of expression, and sometimes rebellion within the black community. Whether it’s being excluded from school or being petted in the workplace by co-workers, black hair has always been political. For many, this over fixation on their hair within majority-white spaces and societies can be exhausting. The film triumphs in showcasing black hair in a space free of prejudice and politicisation.

The decision by Cherry to remove Zuri’s mother from the majority of the film, having her away at the hospital is an integral part of the plot, mainly due to her illness being one which causes hair loss. With hair being central to the plot, the decision to have the only other female character – more importantly Zuri’s mother – could be an intentional ploy by Cherry to open up discussions on the importance of hair within womanhood. Zuri’s mother is seen self-consciously looking at

her head scarf in the mirror, and patting it with a tentative look on her face. With hair being such an integral part of women’s identity- salons often being vibrant social hubs of the community- Zuri’s mother understandably seems lost as she stares at herself in the mirror. However her mood is instantly lifted when Zuri shows her mother a picture she has drawn of her, with a crown on top of her bald head. Upon seeing the picture, Zuri’s mother appears to become emotional and immediately takes off her hair scarf. For many women, their hair is a great source of value when it comes to their self-image. As Cheryl Thompson puts it in her 2009 essay Black Women and Identity: What’s Hair Got to Do With It – “For young black girls, hair is not just something to play with, it is something that is laden with messages, and it has the power to dictate how others treat you, and in turn, how you feel about yourself”.Hair loss for many black women can be an isolating and confusing experience, with many feeling a sense of identity lost along with their hair. Black women’s hair is so often held up against eurocentric standards of beauty – it is estimated that 70% to 80% of black women chemically straighten their hair. Cherry, through his inclusion of Zaya’s mum, pushes a standard of beauty which is outside of these euro-centric and sexist standards, one in which women can feel beautiful with thick, curly hair or no hair simultaneously.

But it would be a crime to overlook the beautiful father-daughter relationship in the film. The journey Zuri’s father undergoes from being an intimidated, clueless beginner, to a supportive, hair-styling connoisseur displays to viewers an unconditional and tender love between him and his daughter. With Zuri’s mother in hospital for treatment, Zuri’s steps into a typically motherly role, which entails doing his daughter’s hair. It’s not often we show the black father in a softer and more vulnerable state. Cherry affords a vulnerability which black men, often hyper-masculine and hyper-sexualised in Hollywood, have not been able to show.His ability to admit defeat after Zuri runs out crying, and try again, is one of the most precious moments in the film. But even more precious is the final scene in which the father and Zuri visit Zuri’s mother in hospital, and present the work of art – Zuri’s hair. Zuri’s hair represents so much more than a hairstyle – it embodies a moment of growth, love and bonding in their father-daughter relationship.

However the best thing about Hair Love is the representation it affords to the millions of Zuris out there – the Dads of Zuris, the Mums of Zuris. It’s refreshing to see a black family in the spotlight, in a plot devoid of trauma and struggle. When I first watched the film, I thought of the younger me, who begged their mum to perm their hair, as to not stand out from friends in high school. If younger me had seen Cherry’s film, perhaps I wouldn’t have been so ashamed of my natural curls. Perhaps I wouldn’t have put it through endless years of harsh heat and chemical treatment. Perhaps I would have accepted the beauty of my afro, instead of trying to hide it. But most importantly, after watching the film, my heart leaps for all the young girls that will see themselves in Zuri and feel empowered – for all the hair love to come.

Mayi Hughes ’23 (anandmayihughes@college.harvard.edu) believes in Hair Love for all.