Last month, Harvard’s Class of 2028—the first to enroll since the ban on race-based affirmative action—began their freshman year. The past few weeks on campus have been marked by discussions following Harvard’s release of the Class of 2028’s racial demographics, which showed that the share of Black and brown students remained relatively stable compared to previous classes. The proportion of Hispanic students increased by 2%, the proportion of Asian students remained fixed, and the share of Black students declined by 4%.

Unlike many other colleges, such as MIT, Brown, and Tufts, which saw drastic drops in the enrollment of marginalized races, Harvard’s results are a welcome surprise despite the drop in Black enrollment. However, experts urge caution in drawing conclusions as confusion around Harvard’s racial demographic data circulates. This year, Harvard reported race differently than in previous years, making it difficult to determine to what extent racial demographics truly changed. Additionally, The Harvard Crimson also found inconsistencies in the data that was reported by Harvard.

Only one thing is certain: regardless of the state of affirmative action, students of color belong on Harvard’s campus. Today, racial diversity is a cornerstone of what makes the University what it is. And despite expert predictions, the results of the Class of 2028 upheld this precedent of diversity. On paper, Harvard’s preservation of racial diversity despite the challenges set forth by the ban on affirmative action is commendable. Harvard affiliates can proudly and truthfully say that campus continues to be a hub of vastly diverse races, religions, cultures, and identities.

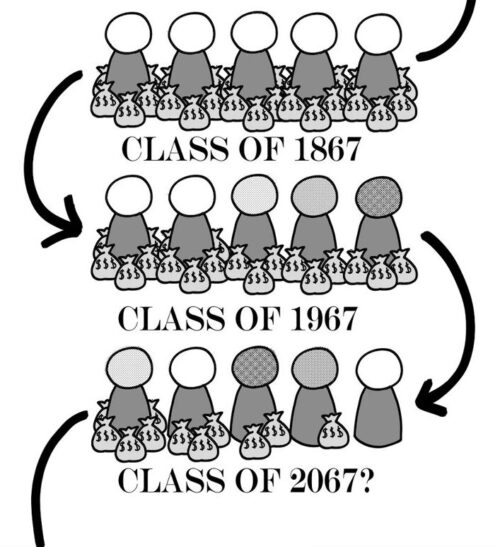

But the reality is not as rosy. Harvard has long used racial representation to obscure its glaring lack of socioeconomic inclusion. In the almost four hundred years since its founding, Harvard continues to be a place for the wealthy. And despite how Harvard showcases its racial diversity, no amount of that can excuse its lack of commitment to socioeconomic representation.

But what do Harvard College’s class demographics actually look like year-to-year? The truth is, there is not a precise answer, because Harvard does not release much information on socioeconomic data. But a 2013 study by Opportunity Insights, a research team at Harvard led by Raj Chetty, reported that Harvard had 15 times as many wealthy students as low-income students. Additionally, a 2018 study led by Richard D. Kahlenberg, a Harvard Law School graduate and researcher, found that a whopping 71% of Harvard’s Black and Latino students come from families in the top 10%.

Kahlenberg has spent years advocating for class-based affirmative action. In an interview with the Independent, Kahlenberg expressed that he hopes that the end of affirmative action will push Harvard and other colleges to consider class-based affirmative action measures for future classes.

“Harvard and other institutions could do so much more to diversify by economic status,” Kahlenberg said. “There’s a lot of talent in America among low-income and working-class students that is not being tapped into, and and now that the Supreme Court has outlawed the use of race in admissions, I think it’s all the more important for universities to look at economic disadvantage as a way of preserving racial diversity and expanding socioeconomic diversity.”

Kahlenberg was an expert witness hired by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) in the Supreme Court trial against Harvard. As a self-proclaimed political liberal and champion of diversity, he is, at first glance, an unlikely member of the SFFA coalition, which is headed by conservative legal activist Edward Blum, garnered high levels of support from conservatives, and was passed by a conservative majority in the Supreme Court. But Kahlenberg’s decision to partake in the trial against Harvard was spurred by his belief in a different type of affirmative action—one based on class—which he hopes will garner more traction now that race-based affirmative action has been banned. “My primary concern is that universities will never pay attention to economic disadvantage in a meaningful way unless the ability to use race is removed,” he emphasized.

During the trial, Dean Rakesh Khurana was asked by SFFA attorneys why Harvard’s student body fails to reflect the United States’ socioeconomic diversity. Khurana’s response was that Harvard is “not trying to mirror the socioeconomic or income [makeup] of the United States… We’re looking for talent.”

I asked Mr. Kahlenberg about his thoughts on Harvard’s justification for its lack of socioeconomic diversity, specifically the claim that increasing economic diversity would lower academic quality. In response, Kahlenberg referenced a simulation that he and his team ran of Harvard’s Class of 2019. In the simulation, the team eliminated legacy preferences and gave an admissions boost to economically disadvantaged students.

“The result was that the SAT scores would go from the 99th percentile to the 98th,” Kahlenberg explained. “Under this scenario, you’d be admitting a lot of students who did not have access to private tutors, to the best public and private schools in America… Many of the students would have had to work to support the family during high school,” Kahlenberg emphasized. “So the fact that the class is at the 98th percentile, even though it has a lot more students who faced disadvantages in life, is really remarkable. I mean, that’s an extraordinary set of students. So I really was not convinced by Harvard’s argument.”

The findings from Kahlenberg’s simulation are promising: by eliminating legacy preferences and increasing the consideration of class in admissions, Harvard College’s Class of 2019 became more socioeconomically and racially diverse, while academic preparedness measures, such as the SAT, remained practically unchanged. The proportion of racial minorities increased from 28% to 30%, while the proportion of first-generation college students increased from 7% to 25%.

“When the litigation was filed, only about 7% of students were first generation college students. And now it’s closer to 20%, so that’s progress,” Kahlenberg said. But he is hoping to see that proportion increase further. Additional simulations that he conducted with Duke professor Peter S. Arcidiacono indicated that maintaining racial diversity would require Harvard to significantly boost the proportion of students from the lower two-thirds of the economic scale—from 18% to 49%.

Class-based affirmative action measures would provide an elegant solution for maintaining racial diversity while increasing socioeconomic diversity. Especially in light of the newly instated affirmative action ban, it is perplexing as to why Harvard has yet to openly discuss the potential implementation of formalized class-based affirmative action.

The answer may lie in financial considerations. Under Harvard’s need-based financial aid policy, financial aid is awarded based on a student’s family income. The less income a student’s family makes per year, the less that student will pay to attend Harvard, with students from families making less than $85,000 per year attending college free of charge. If Harvard were to prioritize increasing socioeconomic diversity, it would lose out on the tuition money that wealthier families would be paying.

Another reason why class-based affirmative action has not gained traction may have to do with the makeup of Harvard’s governing bodies. Notably, under Kahlenberg’s proposal, all forms of legacy admissions would be eliminated; this includes preferences for the children of Harvard alumni and faculty, as well as the elimination of the Z-list, which is a deferred admissions pool for students who must take a gap year before enrolling and favors primarily white and legacy students. The Harvard Corporation and the Board of Overseers are Harvard’s governing bodies, which each play a role in the University’s decision-making and policy. Many of their members are Harvard alumni who come from families with histories of ties to the University.

In a similar vein, donor influence could be hindering the adoption of class-based affirmative action. Donor families contribute significantly to the University’s endowment, and eliminating legacy admissions while prioritizing lower-income applicants could risk losing the financial backing of current donors, as well as future support from their descendants.

Kahlenberg says that Harvard should be disclosing more information about the socioeconomic makeup of its student body. “I think it would be good to disclose, at the very least, the family income of students by quintile,” he stated. “I think that’s something Harvard should disclose on an annual basis.”

For too long, Harvard has masked its overwhelming wealth concentration behind its racial diversity numbers. Now that race-based affirmative action has come to an end, it is time for Harvard to finally address its deficiency in socioeconomic diversity. There is no excuse for Harvard to continue maintaining such low proportions of economically disadvantaged students.

“I think both racial and economic diversity are important on college campuses, and places like Harvard have done the first without the second,” Kahlenberg expressed. “My hope is that over time, Harvard will draw on the talent from people across the socioeconomic spectrum, rather than have it concentrated so heavily toward those from wealthy backgrounds.”

Abril Rodriguez Diaz ’26 (abrilrodriguezdiaz@college.harvard.edu) is the Forum Editor of the Independent.