In December 2023, shortly after my acceptance to Harvard, I traveled to Poland to visit all six Nazi extermination camps—where over 2.7 million people were murdered, the majority of them Jews. Those two weeks were emotionally exhausting and grueling. My instinct afterward was to mentally lock the experience away, to avoid confronting the weight of what I had seen.

However, just a week before spring break, a discussion in my class “Gen Ed 1131: Loss” resurfaced those memories.

“Would you care about what was written on your tombstone?” someone asked. Another student quickly answered, “Epitaphs are for family and friends—to give them closure and the right image of who you were. Personally, I wouldn’t mind, since I’d be dead.” I sat with that for a moment. To me, caring about what’s written on your tombstone isn’t about vanity—it’s about legacy. It’s about wanting to live a life that mattered, that left something behind.

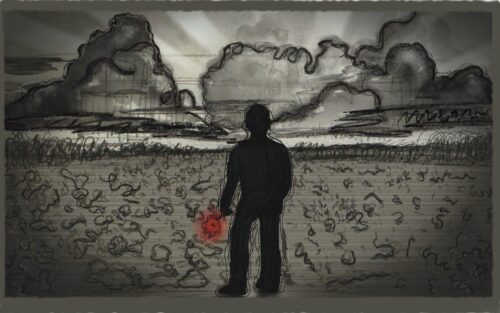

And suddenly, I was back in Poland. Specifically, Treblinka—the second-deadliest Nazi extermination camp. I remember with vividness the deafening silence of the field—17,000 stones scattered across the grounds where the extermination camp once stood. Some of the stones are etched with the names of towns and villages, places from which people were deported. But the vast majority are unmarked—symbols of the individuals whose identities were lost forever.

More than 800,000 people were murdered at Treblinka by the Nazis. They never had the privilege to wonder about legacy, to wonder what might be written on their tombstone, what would be said at their funeral, or to even live a full life. At the center of the memorial stands the main monument, inscribed with the words “Never Again,” in Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, German, French, English, and Russian: קיינמאָל מער, לעולם לא עוד, Nigdy więcej, Nie wieder, Plus jamais, Never again, Никогда больше.

The first camp we visited was Stutthof, near Gdańsk. There, I saw a preserved gas chamber for the first time. Its walls were marked with blue streaks—Zyklon B residue. I stood in that space, overwhelmed. How is someone supposed to process that? I still don’t know.

I kept wondering: How many people my age had stood here? People just like us, worrying about their future, thinking about who they wanted to become, and what they hoped to do in the world.

I couldn’t even claim to be empathetic—how could I be?

How would I react to watching the life and hope slowly drain from the faces of the people I love? To wake up one morning and find them gone during routine inspections—or worse, to wake up beside them and realize they’re no longer breathing?

What would go through my mind in those final moments, as exhaustion overtakes me? As hope flickers out, the will to live unravels, and the boundaries of humanity blur? Under such conditions, the significance of life begins to crumble. What is life? What is humanity?

It doesn’t make sense. In other extermination camps such as Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau, you could see—just beyond the barbed wire—houses, neighborhoods, signs of ordinary life. During the war, residents living near Auschwitz saw the smoke. They smelled the ashes of burning bodies. How is this possible? But even in the darkest depths of despair, there are instances of human greatness—moments of hope that shine so brightly that they defy words.

Among the 17,000 stones at Treblinka, only one bears a name: Janusz Korczak, also known by his pen name, Henryk Goldszmit. A doctor, educator, and writer, he cared for the orphaned children of the Warsaw Ghetto. When offered a chance to escape deportation, he refused. Instead, he stayed with the children, walking with them toward the unknown. He would not let them face death alone.

In the face of genocide, a man chose love, loyalty, and selflessness. If that is possible, then I am proud to be human. But it’s this contrast—the capacity for both monstrous cruelty and extraordinary grace—that again raises those same questions: What is life? What is humanity?

The Holocaust is filled with stories like Korczak’s. Scattered among the ashes are testimonies of resistance, kindness, and moral courage—proof that even in our bleakest chapters, we are capable of greatness.

Going back to the original question about tombstones, I believe we all carry an inherent motif—a desire to say, “I was here.”

I was here.

“I was here” is an acknowledgment of our existence.

A quiet rebellion against invisibility.

A basic human need to be seen, to be known, to matter.

The power and beauty of recognizing one’s own uniqueness and place in the world were taken from the people buried beneath those stones—and continue to be taken from countless others today. The importance of memorials lies in our recognition of their human rights. We grieve and mourn the unjust, inhuman way in which they died. We fight to preserve history so that it never happens again.

And we honor them by saying, “I was here”—for them.

In the aftermath of such loss and horror, it’s natural to question whether life has any meaning at all. And maybe that’s where existentialism offers us something profound—not a denial of meaning, but an invitation to create it. The meaning of life isn’t something we find; it’s something we build. And by choosing to remember, to reflect, and to act, we begin to write our own answer to the question: What does it mean to be human?

For me, it means trying to live a life of remembrance, passion, and fulfillment—a life that, one day, will firmly say: I was here.

Marcel Ramos Castañeda ’28 (mramoscastaneda@college.harvard.edu) is grateful his mom took him on that trip to Poland.