Being Hispanic and Mexican, I do not celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month. Through its materialization at Harvard, the month of September—filled with themed HUDS recipes, house community events, and cultural showcases—prompts contemplation on the interplay of race, culture, and linguistic identity from its Latino students. To me, the month-long attribution feels violently reminiscent of the Spanish colonization of the Americas and simultaneously a recolonization of the Latin American independence days that overlap with it.

Even the title imposes serious neglect. The term ‘Hispanic’ technically refers to Spain or to Spanish-speaking countries, disregarding any disparities between cultures and ethnicities on the grounds of a shared language. As a result, the term “Hispanic Heritage Month” excludes millions of non-Spanish-speaking Latin Americans, particularly indigenous populations concentrated around Central America. Despite the erasure of indigenous languages over hundreds of years, 560 indigenous languages are still spoken in Latin America, with 8.5 million individuals alone speaking Quechua as their home tongue. ‘Hispanic’—a term that perpetuates the European colonialism of Central and South America—attempts to group two vastly dissimilar regions, and the myriad cultural, linguistic, and ethnic identities within them, into one umbrella term.

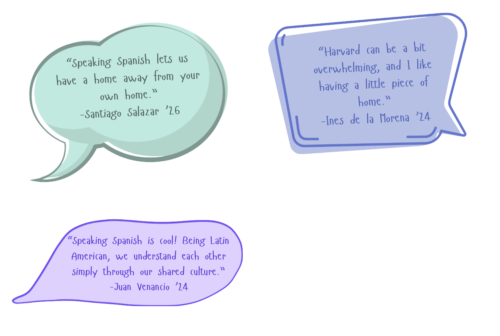

“Latino” more accurately acknowledges geographic and cultural roots. Juan Venancio ’24, president of Harvard Association for Cultivating Inter-American (HACIA) Democracy, shared his perception of being labeled Latino versus Hispanic. “I define being Latino as someone who comes from the region, not necessarily someone who speaks Spanish, but obviously our identity is very complex.”

Venancio feels more Latino than Hispanic. “Academic literature states that the term ‘Hispanic’ originated from the American government in the 1960s,” Venancio explained. The emphasis on “Hispanic” is culturally Eurocentric and perpetuates existing instances of linguistic discrimination that contribute to welfare issues across Latin America. “One can argue that ‘Latino’ came from the Latin American community—which, after many revolutions and uprisings, fought to search for and find this identity,” he says.

Hispanic Heritage Month was first established in the 1960s when President Lyndon Johnson, in tribute to Hispanic Americans, declared Hispanic Heritage Week beginning on September 15th. In 1987, Rep. Esteban Torres of California submitted H.R. 3182, a bill to expand it into Hispanic Heritage Month, and it was enacted into law under President Ronald Reagan in 1988. It is a national holiday—invented and celebrated within the bounds of the United States.

Yet the period of its duration, from September 15th to October 15th, does not reflect a month that is culturally, politically, or socially significant for “Hispanics” or “Hispanic-Americans:” the very community it seeks to recognize. The United States Library of Congress states that the first day of Hispanic Heritage Month is “the anniversary of independence for Latin American countries Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. In addition, Mexico and Chile celebrate their independence days on September 16 and September 18, respectively.” But this pays no homage to any of these countries—if anything, it memorializes American colonial power and takes away meaning from a sacred day of celebration.

Beginning Hispanic Heritage Month on these independence days mirrors the American commemoration of Cinco de Mayo: turning unique, pivotal moments in history into opportunities for Americans to naively celebrate “Hispanic” culture. You won’t find Mexicans celebrating our independence on the fifth of May (a date that actually marks the Mexican triumph over France at the Battle of Puebla), but you will on the night of September 15th and all through September 16th—our actual Independence Day. The true history, culture, and significance of the Latin American struggle and independence from Spain is far from correctly acknowledged in the United States—if anything, it is drowned out by the start of Hispanic Heritage Month, and eclipsed by American holidays like Cinco de Mayo.

The exclusionary nature of Hispanic Heritage Month is particularly significant within Latino communities, since linguistic discrimination is a significant, widespread issue within Latin America.

“My identity has really confused me for the past 22 years. I don’t feel Mexican or Spanish, but rather like a strange mix of a third category,” said Ines de la Morena ’24, who grew up in Mexico City with Spanish parents.“I grew up with Spanish traditions, food—my friends would make fun of my vocabulary—but then when I go to Spain, everyone tells me I’m very Mexican.”

“Ideologically and culturally, I definitely feel more Mexican, but that’s because I grew up and was born there,” de la Morena says.

“I feel like Harvard is a campus with a lot of incredible opportunities, and sometimes it’s difficult to know what’s a good fit,” De la Morena continued, explaining how Harvard has given her a sense of place. “But the good thing about HOLA (Harvard Organization for Latin America), HACIA (Association for Cultivating Inter-American Democracy), and any other Spanish-speaking community is that if you’re Latin American, you know it’s a good fit. You will always have a good time and meet very interesting people. The opportunities at Harvard often revolve around identity exploration, but those cultural groups remain an anchor.”

At Harvard, the circumstances that characterize “Hispanic” as an exclusionary or inclusionary term are entirely different, because Harvard is a Latino-minority space. The topic of Spanish as a language is constantly present at the forefront of my mind. At Harvard, the celebration of the Spanish language is a gateway to beautiful culture—to togetherness, to nearness, to informality, to family, to music, to dance. It is a crisp, refreshing difference from thick, heavy English, sterile classroom talk, formal Harvard speak.

At such a foreign and frightening place like Harvard, speaking Spanish has been the single biggest piece of home that I can carry with me at all times. It can never be lost, and it can never be taken. Perhaps this is why people with shared home-languages tend to group together—our language is a vehicle for promoting shared culture and establishing a sense of place. Just like Venancio says, “People from countries in the region understand each other simply because of our shared culture.”

Somehow, those of us with strong ties to the language find ways to speak more Spanish than English throughout the day—not to exclude others, but to bring our homes to Harvard. I live in a Hispanic suite, and so I am fortunate to wake up to Spanish and fall asleep to it. At the end of the day, being part of a Hispanic community is the single most incredible part of Harvard.

Abril Rodriguez Diaz ʼ26 (abrilrodriguezdiaz@college.harvard.edu) is still proudly celebrating her country’s independence day, which fell on the 16th of September.