Trigger warning: mentions of suicide.

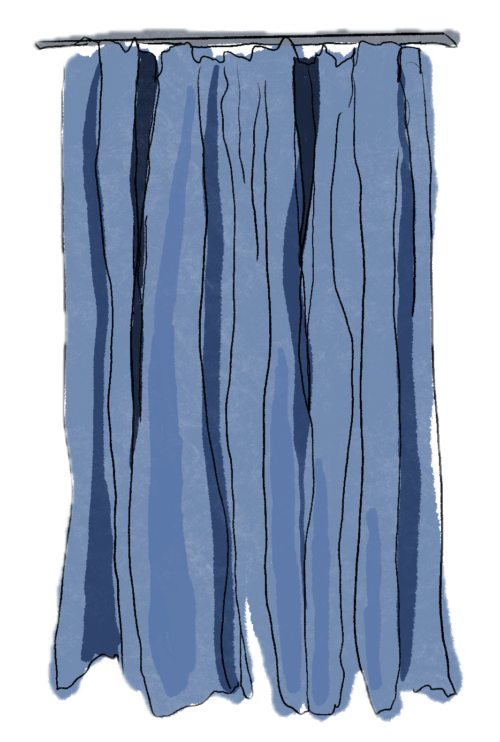

We remember hospitals to be quieter than they truly are. Their hallways form “private rooms:” large spaces partitioned by sheets of blue instead of walls, so that while a patient might not see anything around them, they hear everything. Footsteps reverberate off the tiled floor while noise grows and fades as nurses walk past. Monitors beep discordantly—some too slow, others dangerously quick. Doctors share brisk words of comfort with their patients and speak in foreign tongues with their peers. No sound is inherently good because we rarely go to the hospital for good things.

Each clattering remains distinct but is soon forgotten. The psyche, in its self-preserving way, discards memories and sensations, making us forget the noises that once scared us most.

I’ve visited family members before in their little curtain rooms. When I was 11, treatment centers always startled me with their constant commotion, yet my relatives lying in critical care beds never seemed to notice the rapid clamor around them. My nine-year-old sister, in the hours before surgery to remove a tumor on her back, needed just a little time to detach from her circumstance. She would focus on her hands, tracing their lines. As I sat on the edge of her frigid, cerulean bed, asking insignificant questions and telling bad jokes, she wouldn’t respond. Her eyes never even met mine. Instead, they remained on her palms as she touched finger to finger, scrutinizing parts of herself that she never regarded as worth her attention before.

Around five minutes before tunic uniforms rolled my sister into the surgery room, a nurse pulled back our curtain, enabling sight of a passerby. A newborn rolled past us in a clear, wheeled box. One wheel seemed to be loose, for the box shook profusely as it squeaked across the floor. The newborn’s ventilator covered her mouth. She laid motionless as a monitor with a straight line emitted a monotonous beeeeep. I didn’t know what that meant, so I turned to my sister, smiling, in hopes of a reaction. “Look at the baby!”

Years later, I asked her if she remembered that baby. She didn’t. I can’t recall if she ever even looked up to see it. Was this a memory she threw away or never had? Should I have thrown it away?

At fourteen, I found myself in my first curtain room for emergency treatment. My school had forced me into a psychological evaluation after classmates had stolen my journal and began spreading rumors about its contents. They began with truths—retellings of my familial pains, iterations of my worst memories. But middle school is when kids learn to feed their cravings for inclusion, gluttonous on external validation. Truths are blended with fiction, so everyone was a part of my story; everyone had a moment of recognition. I suppose I wanted that too, but that chance was lost to malicious translations. While worse narratives travelled, the only one my school cared about was my accused suicidality.

I spent nine hours in the emergency room, six of them alone. Four psychiatrists visited me individually, each asking things of me that I can’t remember. I recall hearing very little, just a distant hum of whisperings. When I tried to engage in conversations with the doctors, I became distracted by my mind’s voice, which oscillated from shame to frustration to shame again. I choked on stifled words like they were phlegmy coughs that I never wanted to be heard. My voice felt dirty, futile. I blamed it and my journal for my circumstances.

In those hours alone, I could find no words at all, only static. Maybe it came from the TV that I couldn’t figure out how to turn off completely. It seemed to distort time, or at least fuse time together, making each hour in isolation indiscernible from the next.

Sight became my only working sense in that curtain room. My family couldn’t visit, so I soon attempted to gain familiarity with each doctor and nurse I met. This practice proved useless; they would inevitably end their shifts and replace themselves with a new white coat two hours later. Their features on any other day would’ve seemed indistinct, but within those nine hours, I memorized the different curvatures of each human nose more than ever before. I was desperate for humanity, just a trace of it—the hospital didn’t feel human at all.

My toes peeked out from a new but already destroyed blanket, which my hands ripped apart little by little in anxious bursts. It was aquamarine, sterile, and when I held it in my fists after tearing it to pieces, I felt that I’d ruined it, dirtied it. I felt dirty. My nails, jagged and untrimmed, pressed into my palms, forming tiny crescents in them. Each finger was too weak, only capable of breaking skin in one little spot that I then began to pick at.

My eyes diverted to an opening blue curtain in front of me as I watched three nurses enter my sheet-covered room, one with a notebook and two telling me something that I didn’t pay attention to. One empty-handed nurse exchanged a glance with the other before stepping forward and holding my arms together. Her touch was firm as she turned my wrists upward.

She pushed me against the critical care bed as the other woman walked forward. Fingers tickled the flesh of my back, and I felt the string of my hospital gown unravel. Instinctually, I pulled my arms into myself in an attempt to break them free of the nurse’s grip, and tried to roll over like a pill bug stuck on its back.

This is the version I tell myself—how I cultivate memories and protect my mind, replacing truth with distortion. But honesty is ruthless. It scolds me, strips me bare: I didn’t fight. I didn’t resist at all. I instead lay there motionless, a living corpse, as bare hands pulled back my gown and lifted my hair, checking my thighs, my stomach, between my toes, for something that was never there.

My head lay on top of the tattered blanket, forcing me to face the nurse with the clipboard. She spoke to the others, jotting something down. I searched her face for anything, no, everything, fixing my gaze on her frowning lower lip, and then to her nose which curved upward and widened at its tip. Maybe if I could see every part of her, she would look at me too, and recognize my mortal pieces, the way my septum deviated to the left. Maybe she would see a girl, a girl who was sad, but wanted to live through that pain and eventually be happy. Maybe she would see a girl begging to feel like a person again.

But she disengaged from the telling parts of me, instead focusing on the color fading from my complexion to avoid the collecting dew in my eyes. Her features blurred beyond recognition as water drowned my scleras, incapable of being wiped away as long as my hands lay held down in front of me. The static in my head turned into nothing, and now I perceived nothing as a sound.

This same nurse returned with her clipboard a few hours later, but by then, I couldn’t look at her any more than I could hear her. Her lips moved, shaping words I didn’t catch. I only learned I was discharged when she turned to my father instead. She told my father what the psychiatrists had decided: depressed, not suicidal. They found no cuts on my body, no words in my journal that suggested self-harm, no movements during the nine hours alone in a curtained room that indicated anything besides the will to persist. I wonder if the nurses said goodbye. I wonder if silence always protected me, or if in moments like these, it made things worse.

I left the hospital at 11 p.m. that evening, marking the ninth hour spent in that little curtain room, and shook violently at the screams of an ambulance’s siren just beyond the exit doors. Cars around me swished as they passed by, and plastic bags scraped against parking lot concrete. A baby—who I later found out had been in the curtained room beside me that day—nuzzled his chin into his father’s arms as the two walked out of the hospital and passed me by. He began to cry, his muffled sobs pushing towards me from the wind. Surely he cried in the hospital hallway, but I had no recollection of hearing that sound before. I’d forgotten the world outside of myself. Finally, I understood my sister, her own lapses in memory, and decided I would choose to remember; remember the baby, remember the nurses, remember the sound of nothing.

When I walked forward past the emergency room, there was no relief in my diagnosis, no resentment for the nurses’ unempathetic touches, but a quiet resignation. For nine hours I hid in a cerulean bed, desperate to disappear into silence, but silence never protected me. It only made it easier to look past my expressions, to replace my voice with a clipboard, and my body with a case file. I let silence steal moments from me, let it erase the sounds I wasn’t ready to hold on to. I still search for echoes of all I’ve lost, each sensation, and hope one day to recover everything.

Anonymous is grateful she can be vulnerable through the Independent.