A year ago, Harvard students faced their first Christmas under COVID-19. At the time, vaccines were still a distant dream, Delta the variant du jour, and Harvard staunchly committed to remote instruction. COVID-19 had completely shaken up everything anyone thought was possible in a university setting. If you got the virus, you and your loved ones were scared and mournful in equal measure, certainly not annoyed. It was, in no uncertain terms, an apocalyptic disease.

Today, COVID is, for many, nothing more than a source of annoying and expensive paperwork. Rower Ethan Seder ’22 explains that crew teams normally go to Florida for training during the winter. “This is the first time [since leaving campus in December] we can really get together as a team and attack the ground and get a lot of training in,” he says. “It’s also training on the water… the Charles river freezes over, so Florida training is so important because it allows us to get our technical skills back.” This year is no exception, and most of the team made the trip south. Seder, however, did not join them, because on a trip to the Bahamas, he tested positive for COVID-19. The way he explains this sounds less scary than it does tedious: “I came here with my girlfriend to travel around and just enjoy the Bahamas… on day five of your travel, the Bahamian government requires you to take an antigen test, and after you get a positive test, you are basically stuck in the country… until you get a negative test, or until day ten, when you can leave.” He describes himself as “just counting down the days until I can rip a negative COVID test,” and is above all annoyed that he cannot be with his team, none of whom, he says, have been interrupted by COVID-19.

Seder is very aware of pandemic dangers: “People want to be safe, obviously, so… Harvard has a very detailed policy as to how to return to school, and I plan on following that policy, whether or not that means I can show up to camp.” However, his planning mostly centers not around the details of the disease itself, but around the high costs associated with the local testing infrastructure. Even in 2022, COVID can present significant financial and interpersonal challenges. In an attempt to circumvent some of these challenges, Seder has developed an “exit strategy,” which involves taking rapid antigen tests daily until he tests negative and only then paying the $250 that it costs for the PCR test that will let him leave the Bahamas. He is also considering extra training to make up for what he is missing: “I try to do the little exercises that you can do in your room, but fundamentally [I’m] pretty landlocked… I don’t think it will be mandated from the coaching perspective, but just on my own accord, I feel the responsibility to get in a lot of training.”

Neither Seder’s troubles, nor those of other Harvard students, necessarily end when they return to campus. MakeHarvard, an annual hackathon centering around building physical devices as opposed to software only—and hence heavily reliant on in-person work—was scheduled for the weekend of January 29th. As Saba Zerefa ’23, logistics chair for MakeHarvard, explains, the team continually reevaluated their plans through winter break, in the light of changing pandemic safety standards. “Initially, the logistics team came up with three levels of contingency planning, as advised by SEAS [Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences] administrators… one in which we invited everyone in the world, including international students, one that was only domestic, and then one that was only Boston-area schools like Harvard, Tufts, Northeastern, and MIT.” At some point, though, they had to choose a level and commit to it. “Typically we buy materials three weeks before the event. The ‘everyone’ event would have been 300 people, so we asked, ‘Do we shop for this, or do we shop for half as much?’” In the end, expecting to invite only domestic students, they purchased supplies for 150 people.

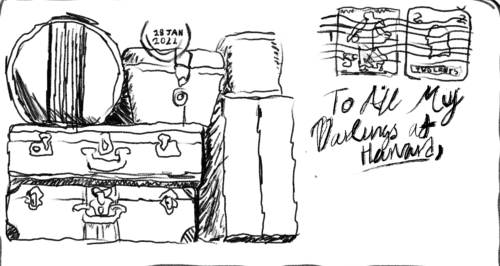

At the time of writing, those supplies were still in the Leverett mailroom. On the 12th of January, the decision was made to cancel the event due to the Omicron variant surge. The push did not come from the greater Harvard administration. Zerefa described Harvard’s guidelines as “very vague… [allowing] a lot of flexibility within specific schools,” and said, “We had several meetings with administrators where they were acting like it would happen.” Rather, Zerefa claims the decision to cancel this year’s Hackathon originated with managers of SEAS or of the SEC (Science and Engineering Complex). (Zerefa is unsure which, but her main contacts were SEC personnel.) In theory, they could have moved the event to the Science Center, Sever Hall, or another non-SEC building, but the logistics would have been too difficult to plan on such short notice.

Requiring regular tests for attendees was also a no-go: “We discussed this, but it was actually very difficult to acquire tests, because of the test shortage.” MakeHarvard was a victim not of a university that could not allow any in-person events, but of a school that did not believe the risk of this one in particular was worth it. Even in the SEC, in-person classes are going ahead, and returning students were given the full run of the campus as soon as they got a negative antigen test.

This year’s COVID-19, then, is not so much a complete change to everything we do as it is simply one more thing that can spoil a plan. Testing protocols for returning students are extensive, requiring both PCR and antigen, but the University requires no isolation without a positive test. Perhaps this is the surest sign that the pandemic is finally winding down: even the administration seems to be treating it as an irritating inevitability, not the terrifying possibility it once was.

Michael Kielstra ’22 (pmkielstra@college.harvard.edu) would quite like COVID to keep out of his plans for this semester.