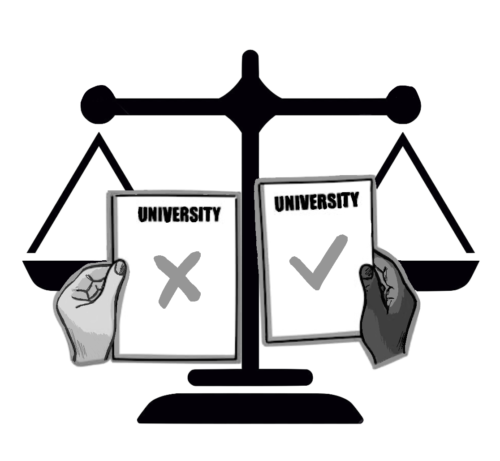

In the wake of the June 2023 Supreme Court ruling addressing race-conscious college admissions, Harvard College’s Class of 2028 is of national interest. Since preserving diversity in American education is essential for high-quality instruction and the democratic strength of our nation, the College is at the forefront of this discussion.

“Everyone wants to know, how is Harvard responding? Are they changing their admissions process? Are they changing their recruiting practices? Has their applicant pool changed?” explained Tyler Ransom in an interview with the Independent. Ransom is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Oklahoma and was a consultant for Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) in their lawsuit against Harvard.

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn affirmative action came in response to accusations that both Harvard College and the University of North Carolina violated the Equal Protection Clause and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Plaintiffs SFFA argued that these schools intentionally discriminated against Asian American applicants on the premise of race. Ultimately, the Court decided that such practices were unconstitutional. This ruling came around two decades after California enacted Proposition 209 in 1996, which ended all state affirmative action policies in education, employment, and contracting.

Considering the Class of 2028 is the first to join the College since the decision, many predicted its demographic composition to demonstrate significant changes, particularly in minority enrollment. However, the Admissions Office released the Class of 2028 profile this past week to reveal remarkably similar numbers.

New demographic statistics for the Class of 2027 were reported in The Harvard Gazette’s recent press release, which re-calculates based on percentages of only students who chose to disclose their race. The previously released statistics calculated student demographic percentages based on overall enrollment.

Using the newly reported numbers, Harvard’s cumulative minority enrollment decreased from approximately 36.7% of the Class of 2027 to 31.5% of the Class of 2028. The Class of 2028 African American or Black student population fell from 18% to 14%. Furthermore, Native American enrollment decreased from 2.2% of the Class in 2027 to only 1% of the Class of 2028. Nonetheless, in comparison to projected enrollment numbers documented in the SFFA v. Harvard lawsuit, the change in class composition is less drastic than anticipated. Ransom explained the predicted shift in minority enrollment following an overturn of affirmative action is expressed in these findings.

“Under the status quo, [the current minority student population] would be about 13% Black and 13% Hispanic. And then, without any racial preferences but everything else the same about Harvard’s process, [the minority student population following an affirmative action ban] would drop to about 4.6% black and 7% Hispanic,” Ransom described. “The Asian numbers would rise from 22% to 29%… The white numbers would also rise from 45 to 51%.”

Economists Dr. David Card and Dr. Peter Arcidiacono predicted similar outcomes if the SFFA ruling were to overturn affirmative action, according to projected enrollment numbers displayed by The Harvard Crimson in 2022.

However, in contrast to the anticipated Hispanic or Latino enrollment, Harvard’s Class of 2028 experienced an almost 2 percentage point increase in such students. Also straying from the anticipated numbers, according to the Gazette press release, “Thirty-seven percent of students [in the Class of 2028] identified as Asian American, representing no change from the year prior.”

Looking at peer universities sheds further light on these statistics. Similar to Harvard, Yale’s Class of 2028 was able to also maintain a diverse student body, with their African American numbers holding at 14% and Hispanic enrollment experiencing an increase from 18 to 19%. In fact, Yale received the most minority applicants ever during the 2024 application season, and its Class of 2028 had the largest share of Hispanic or Latino students in the University’s history. However, unlike Harvard’s profile, Yale’s Asian American student population dropped from 30% of the Class of 2027 to 24% of the Class of 2028.

MIT starkly differentiated from Harvard and Yale, observing concerning falls in their minority populations. The percentage of African Americans in the Class of 2028 in comparison to the Class of 2027 dropped by 10 points. The share of Hispanic or Latino students fell by 5 percentage points, and MIT’s Asian American enrollment increased by 7 percentage points.

Amherst College observed similar shifts, with the proportion of African American students in the Class of 2028 falling to a mere 9%—a tremendous decline from the 19% enrolled in the Class of 2027. These inconsistencies have prompted questions about how Harvard maintained such a diverse student population when other elite institutions and academic studies found or forecasted the opposite. And while it is difficult to understand such numbers without full transparency regarding legacy preferences, athletic recruitment procedures, racial data calculations, and other admissions criteria, there are a few suspected reasons behind such results.

First, Harvard’s methods of calculation changed in the wake of the Supreme Court decision. When sharing the demographics for the Class of 2028, the College used a denominator that excluded international students and those who opted to not disclose their race. This decision inevitably shifts student enrollment percentages, making it harder to understand the current first-year profile in the context of information from prior years.

Ransom also articulated that, “Universities are probably going to change the weights that they put on different applicant attributes to arrive at the admissions decision.” In the context of Harvard, the application for the Class of 2028 experienced a significant overhaul. Eliminating the supplemental, optional essay that let applicants write on any topic of their choosing, Harvard instead added five required short-answer questions focusing on topics ranging from life experiences and extracurriculars to attributes a prospective student would want their future roommate to know about them. Ransom suggested that these changes may have been made so the admissions committee could shift some of their decision-making to student essays and other more holistic factors rather than concrete metrics.

Additionally, when understanding the projected enrollment numbers, Ransom explained that a lot has changed since that data was released. The figure used in SFFA v. Harvard was calculated from 2019 Harvard student demographics yet the Harvard Class of 2027 observed significantly more African American and Hispanic or Latino students than 13% each. Furthermore, when analyzing schools like MIT, it is important to remember that allowing multi-ethnic students to check more than one box when self-reporting their racial identity also complicates how these numbers can be interpreted year-by-year. MIT’s Class of 2027 reported demographics totaled 112%, whereas its Class of 2028 racial percentage breakdown only reached 101%. Harvard has also been altering how multi-racial students document their ethnicities, further muddling the impact of the Supreme Court ruling.

According to Ransom, we cannot fully understand the gravity of the Supreme Court decision without the complete applicant data, which will likely be published by the Department of Education in a little over a year. “I actually don’t put much stock in those numbers as being informative of anything. I think that we need to just wait until the official government numbers come out,” Ransom expressed. “I view all of these releases as more of a public relations campaign than actual information.”

“While the admissions offices at these places, they’re trying to kind of play the middle between, ‘We have some really strong feelings on the pro-racial preferences side from our alumni and from our faculty and other stakeholders,’” he explained. “‘We also have a lot of people on the anti-racial preferences side that are really wanting to make sure that we’re adhering to the ruling.’ And so they’re just basically trying to appease both sides.”

Ultimately, American universities are stuck between a rock and a hard place as they attempt to maintain a variety of cultural backgrounds among their students while remaining racially neutral in the application process. Ransom suggests that increasing a school’s “recruitment of applicants” is a possible solution. In a letter to the Harvard community following the release of the Class of 2028 data, Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Hopi Hoekstra explained how Harvard would be doing just that.

“Last fall, the Admissions team increased recruitment travel programs and outreach to school counselors and community-based organizations and further expanded outreach to rural communities in the South and Midwest, advancing our core goal of encouraging a diverse group of promising students, regardless of background, to consider Harvard,” she wrote.

Harvard promotes the sentiment that “We all belong here.” In the aftermath of these past few years of intense scrutiny surrounding the University’s competitive admissions process and in advance of the inevitable future impact of the affirmative action ban, it is unclear how Harvard plans to uphold this motto. Yet William R. Fitzsimmons, dean of admissions and financial aid, assured the student body that the school will not stray from this commitment in a statement in the Gazette.

“Our community is strongest when we bring together students from different backgrounds, experiences, and beliefs,” he said. “And our community excels when those with varied perspectives come together—inside and outside of the classroom—around a common challenge by seeing it through another’s perspective.”

However, the coming college application seasons will be telling as student enrollment numbers become increasingly transparent and previously notoriously secretive institutions are forced to bring their methods into the public eye. And, as Ransom explained, “It’s not just about what’s happening with what Harvard’s allowed to do in the admissions process.” As an elite institution, Harvard’s actions will set the tone for the future of the cultural enrichment and quality of the American higher education system.

Sara Kumar ’27 (sjkumar@college.harvard.edu) writes News for the Independent.