In the depths of Annenberg dining hall my freshmen year, only inches of wooden table separated me from a newfound friend. But with one word, one piercing assumption, that distance became a mile.

“So, where are your parents from?” they asked, wide-eyed and earnest.

Parents. The dreaded plural. My heart jumped into my throat; my mouth went dry. The dinner conversation suddenly felt like an interrogation. I searched for the right response, some way to deflect the question and move on to another topic, but I didn’t have time. I couldn’t hesitate. So I let out a colossal lie.

“My mom is from Arkansas and my dad is from Kansas,” I said. Is—the present tense. It was all I could muster without dropping the ultimate conversation bomb of, actually, my dad died four days before I moved into my freshman dorm. I forced a smile, and said, “What about you?”

Our conversation had begun with a simple discussion of classes and social life, a ritual performance I mastered in my early days at Harvard. But with the delivery of a single, well-meaning question, it took a turn to the deeply personal, a plunge into a cold ocean whose waters I immediately yearned to escape. This required a type of performance that was foreign to me—pretending my dad was alive.

The coronavirus pandemic has cast a dark shadow of bereavement across the United States. Roughly 1.2 million Americans have lost a close relative to COVID-19, according to a July 2020 study from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US. Emily Smith-Greenaway, one of the study’s authors and a sociologist at the University of Southern California, helped conceptualize those numbers: “For every COVID-19 death, nine individuals are left without their grandparent, parent, spouse, sibling, or child.” The emotional ramifications of this “mortality shock” are yet to be measured.

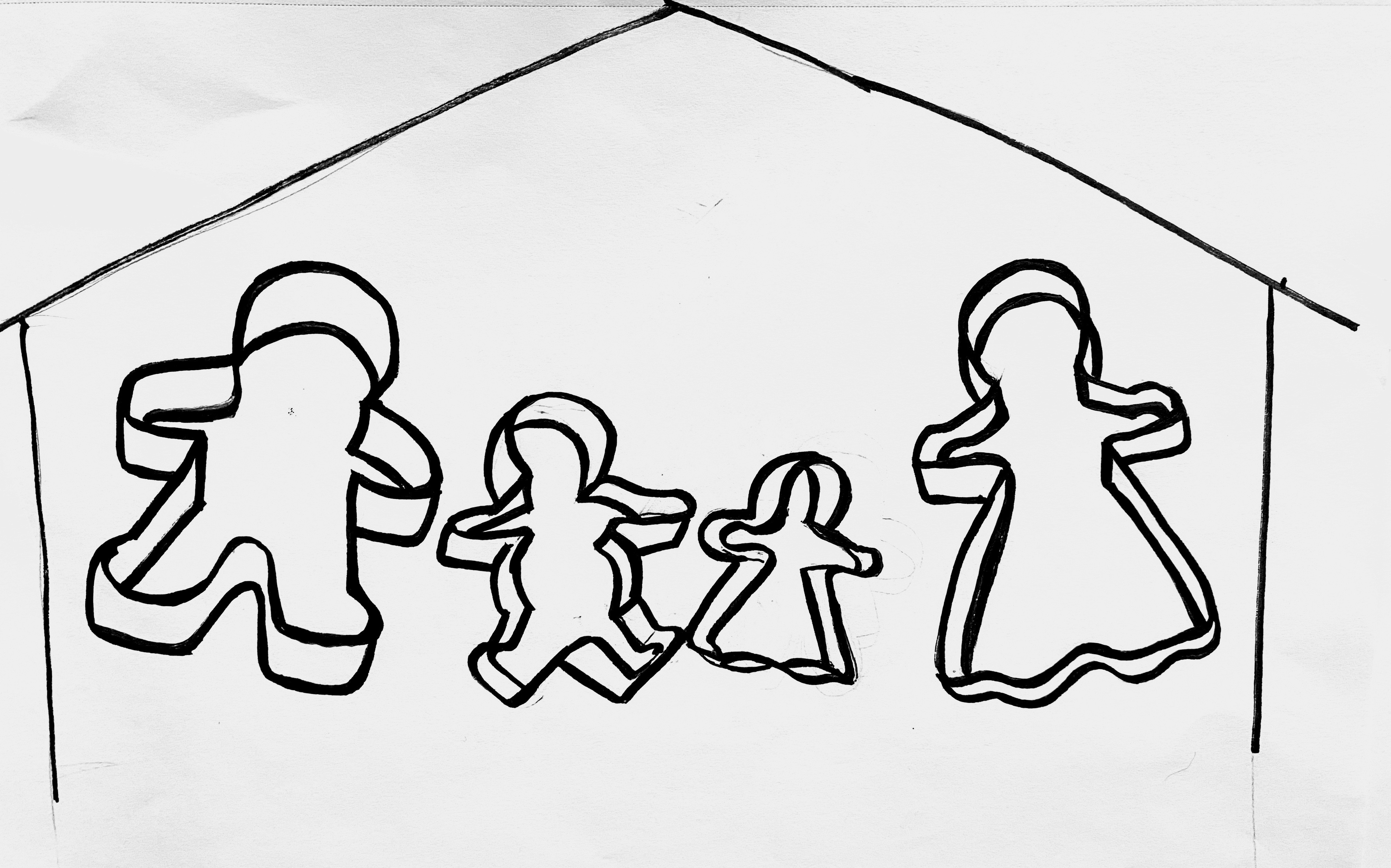

In these grim times, we must widen our understanding of family, for the sake of those grieving and to better recognize the unorthodox structures many of us call home.

The nuclear family—a basic social unit containing a set of parents and their dependents—is far from a universal reality. In the American postwar period from 1950 to 1965, nuclear families flourished and familial “togetherness” became a national ideal. However, after 1965, “nuclear families fragmented into single-parent families, single-parent families into chaotic families or no families,” David Brooks writes in a March 2020 article of The Atlantic. In 1960, just 13 percent of all households were single-person households, census data indicates. By 2018, that figure had grown to 28 percent. “We take [the nuclear family] as the norm, even though this wasn’t the way most humans lived during the tens of thousands of years before 1950, and it isn’t the way most humans have lived during the 55 years since 1965,” Brooks notes.

Yet at Harvard, the expectation that all students go home to a set of two parents prevails.

“We like to pretend we’re more considerate or caring, woke even, that we don’t let society’s standards define how we treat others, and in many respects, that is true,” said Tanner Humphrey ’23. However, he pointed out that for those students living in a non-traditional family situation, “any conversation about living off-campus can become a minefield of complicated feelings and challenging, often awkward, conversations.”

This tension stems from an inability to relate. If the cultivation of human connection is based on shared experiences, it’s harder to form friendships with people who come from different backgrounds—especially during a student’s first days on a college campus.

“Every new relationship is another instance in which you could need to explain why your life doesn’t look quite like everyone else’s; every conversation another opportunity to feel like the outcast,” Humphrey said. “The surprised looks and expressions of pity aren’t usually helpful.”

These feelings of exclusion might emerge during conversations like the one I had in Annenberg. They were also triggered in Spanish class, when my teacher asked me to describe my parents using newly acquired vocabulary words—madre and padre. And during first-year family weekend, when new acquaintances exclaimed, “I’m so excited to meet your parents!” The list goes on.

When the vast majority of Harvard students were sent home in March due to the pandemic, the assumption of the nuclear family became particularly prominent.

“I can’t tell you how isolating it was to watch classmates, professors, and administrators consistently normalize a narrative of moving back into your childhood home with two parents who formed an integrated financial unit,” a Harvard sophomore shared with me. “I was not okay, my experience was vastly different from the ‘pandemic narrative’ that everyone seemed to be talking about, and I did not feel like it was something I could talk about with anyone.”

For this student, moving back home during the pandemic brought various challenges, including bouncing between homes and family members and facing financial estrangement. Since they could still access WiFi and had a place to live, the student thought Harvard would deem a request for housing accommodations unnecessary. They now live in Boston with roommates.

“While we were on campus, Harvard did an adequate job of providing “family” and “home” for those of us who lacked it,” the student said. “But after the pandemic, there seemed to be so little understanding that for many of us, Harvard was not a second home, but in fact the only stable environment we had to turn to. While there is no way to fully rectify that situation during remote learning, it could at least have been acknowledged so that we would feel less alone and less like anomalies.”

Humphrey echoed a similar sentiment. “It’s not always okay to assume that another’s life looks exactly like yours,” he said. “What might not seem familiar to you could be all another knows.” To cultivate more inclusivity at Harvard, “a recognition of the fact that we all don’t live the same life could go a long way,” he said.

That night in Annenberg, my new friend and I continued our conversation uninterrupted by the awkward silence that a comment about death would inevitably provoke. I left the dining hall feeling, in part, satisfied. By repressing my most painful truth, I saved my friend from discomfort, and sheltered myself from needless emotional exposure.

Deep in my stomach, however, I felt unsettled. Did I betray my father by lying about his existence? He would’ve wanted me to own the fact that he was no longer here to honor the life he lived. On the other hand, how could I be so vulnerable in front of someone I had just met?

This moment was more than just a conversational dilemma—it was an insight into the assumption about nuclear households that feels instinctive for many of us. Even I sometimes mistakenly refer to my parents in the plural and present tense.

But given the rising coronavirus death toll and the spotlight that virtual learning has placed on home life, we ought to rethink outdated expectations about family life. Let’s start to acknowledge the different environments we each come home to, and perhaps we can reduce the distance between us all.

Mary Julia Koch ’23 (mkoch@college.harvard.edu) writes Forum for the Independent.