BY KATE TUNNELL ’24 AND CAROLINE HAO ’25

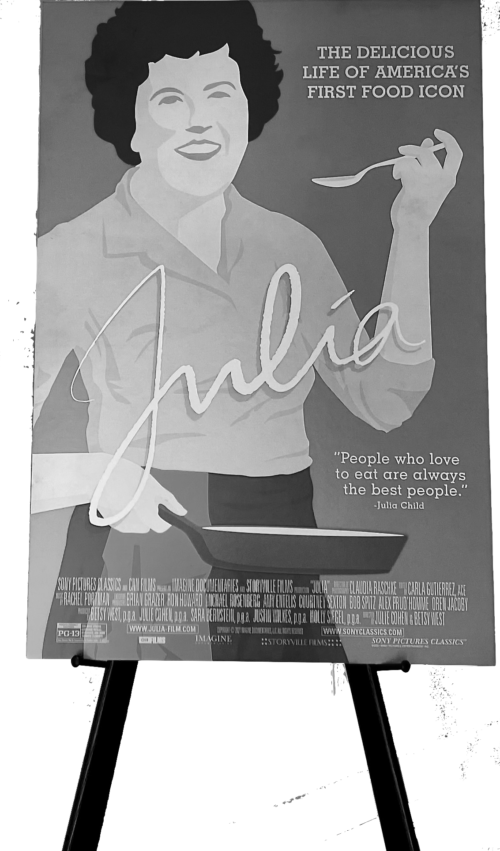

Many hit films and TV shows have sought to capture Julia Child, an American chef and television star who rose to fame in the 1960s. But none have portrayed the culinary titan quite like JULIA, a documentary that aims to reconcile her career and legacy. The Independent sat down with co-directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West at a roundtable discussion of college journalists and had the opportunity to preview the film before it hits theatres on November 15th.

Cohen and West strolled into the conference room at the Hotel Commonwealth in Boston, smiling enthusiastically. “Was this organized?” asked Cohen, referring to the fact that all the journalists in front of them were women. We laughed nervously, wondering what brought the girls next to us here. Did we all come because we like cooking? Or because we love Julia Child?

Cohen and West had previously worked together on multiple documentaries, including one on the life and accomplishments of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, and another on Pauli Murray, an American civil rights activist and lawyer. When asked why they landed on Child as the focus of their next film, West responded: “She was somebody who changed the way Americans thought about food, the way Americans thought about television, and even the way Americans thought about women.”

JULIA explores the stereotype of the ’60s housewife, who was expected to serve as a caretaker to her husband and children—cooking, cleaning, and tending to their needs. Women were seen as delicate and timid, and when they appeared on television, they dressed in frills and played accompanying roles to men.

Julia Child contradicted these gender expectations. “Julia was a gregarious person,” said West. The film depicts her as a rowdy, loud, self-made woman whose personality was broadcasted on countless American televisions. Her cooking show, Cohen explained, “was not the result of a bunch of executives making a big plan… it was Julia herself who connected with an audience hungry for authenticity.”

Authenticity—there couldn’t be a more perfect way to describe Child. As the documentary illustrates, she was relatable, entertaining, and unapologetically herself, which was why people loved her so dearly.

Child’s celebrity status also sprung from her impact on American cooking. She transformed complex French dishes into written recipes for the everyday American. Her wildly successful debut cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961), articulated the steps of making robust beef bourguignon and decadent tarte tatin. Child showed people what they could accomplish in their kitchen—a place for more than jello platters and spam, but for art, excitement, and even a profession.

One of Cohen and West’s favorite discoveries about Child was her unconventional relationship with her husband, Paul. Subverting the stereotypical gender dynamic, Paul played a supporting role in Child’s life. He encouraged her career, praised her ambition, photographed her, and helped with her film sets, evident through the stunning photos he captured of Child over the years.

Despite these elements that distinguished Child from conceptions of the typical woman, the directors noted that if cooking weren’t the subject of her show, she likely wouldn’t have accumulated the fame she did. “It’s not too radical to have a woman expert at least be wearing an apron and whisking in the front of the stove,” said Cohen. “Had she been an auto mechanic, she probably couldn’t have even gotten a TV show on a local PBS station.” Nevertheless, “we see Julia’s story as very much a feminist story.”

Child, however, did not call herself a feminist. “Women’s empowerment was always ridiculed and dismissed by society at the time,” said Cohen. “‘Feminist’ was the F-word,” added West. Child was afraid to assume the label due to its possible impacts on her professional career, and she initially kept her television persona exceptionally apolitical.

As years passed and Child grew more comfortable with her fame, she began to use her significant following to advocate for progressive ideas and policies. In 1982, she penned a letter expressing her support for Planned Parenthood. “Few politicians will take the risk of publicly supporting either contraception or abortion—and who is ‘for abortion’ anyway? We are concerned with freedom of choice,” she wrote. Child also traveled the country, leading a series of cooking classes to fundraise for the cause.

Julia Child rose to fame behind a kitchen counter wearing a cooking apron. If she were to exist today, she likely would not be considered nearly as revolutionary as she was decades ago. But during her time, she broke barriers where they could be broken. In JULIA, Cohen and West contextualize and memorialize Child’s groundbreaking achievements in the culinary arts and women’s empowerment. She inspired female chefs and those they fed to cook, to eat, to live, and to love. As she wrote in My Life in France: “try new recipes, learn from your mistakes, be fearless, and above all, have fun.”

Kate Tunnell ’24 (katetunnell@college.harvard.edu) and Caroline Hao ’25 (carolinehao@college.harvard.edu) hope to recreate a few of Child’s recipes soon.