My favorite essay of all time is “Simone Weil” by Susan Sontag, from her watershed 1966 essay collection “Against Interpretation.” Here’s the first line, for a taste:

“The culture-heroes of our liberal bourgeois civilization are anti-liberal and anti-bourgeois; they are writers who are repetitive, obsessive, and impolite, who impress by force—not simply by their tone of personal authority and by their intellectual ardor, but by the sense of acute personal and intellectual extremity.”

At a Barnes & Noble in Manhasset, N.Y., my brother Adam picked “Against Interpretation” off the shelf, handed it to me, and instructed me to read that first line back to him. Halfway through, he interrupted me and finished it himself from memory. He watched me intently as I paged through the rest of “Simone Weil.” When I put “Against Interpretation” back on the shelf next to “On Photography,” he told me I must not have read the essay closely enough. If I had, he said, I would have had a more noticeable reaction.

If I remember correctly, this happened last summer, or maybe in the spring. Either way, looking back, I situate my only cursory glances at Sontag’s essay somewhere in the seemingly infinite, indivisible time frame between Ivy Day 2024 and the onset of my first fall semester. Those five months, fused by their aimlessness and interminability, could not have clashed more tonally with Sontag’s essay. I would have to wait until freshman spring for “Simone Weil” to gain real salience with regard to my course readings and, to the chagrin of my friends, everyday discussion.

In History & Literature 90ER: “The Gilded Age,” I was presenting to my seminar about neurasthenia in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I was suddenly struck by a distant memory of another line of the first paragraph of “Simone Weil:”

“Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness.”

Oh, my god, that was so many quotation marks.

I won’t go into why that’s relevant to Gilman’s short story (if you’re interested, find me and inquire directly). A friend of mine came up to me after class and called my point “heady,” and I took that as a compliment. What’s important, however, is that at that moment, Sontag’s essay began to seep into conversation.

That night, I went back and reread the full essay. Twice.

Shortly after, at Annenberg Brain Break, something somebody at my table said caught my attention. I have no recollection of what they said, but minutes later, I was summarizing the first paragraph of “Simone Weil.” The next day, in a discussion about Augustine’s “Confessions” for Humanities 10b: “A Humanities Colloquium from Homer to Joyce,” I reluctantly (who am I kidding? It wasn’t reluctant) brought up a point from that essay—that every truth “must have a martyr.” I didn’t specify Sontag as the origin—rather, I implicitly attributed that idea to the literary ether.

My friend Elise pointed out to me recently that much of my humor is referential. That’s true. Nothing sparks more joy for me than weaving two or three disparate threads of thought into one succinct joke, except for perhaps the laughter of those around me after a successful delivery. For the next few days, I made overly convoluted associations between the goings-on in my friends’ lives and bits of Sontag’s wisdom, to much admiration and applause.

For whatever reason—maybe I just wanted to be meta about myself—I began to wonder what underlay the humor of the callback. Perhaps referentiality is the hallmark of a humanities education—from elementary school, we’ve been taught to read books not in a vacuum but in dialogue with other texts. Referentiality is a universal skill unconsciously inculcated within us by even our earliest English classes, and the ability to channel it into humor is a natural outgrowth of that education.

“The White Lotus” and “30 Rock”, two shows replete with nods to literature, culture, and even themselves, are as renowned as they are in part due to their referentiality; they make the viewer feel accomplished for understanding callbacks when the viewer hasn’t actually done all that much. No matter the media—literature, film, historical writing—we’re trained to identify and appreciate moments when consumption of other works is necessary to grasp the breadth of whatever point is being made. Put simply, we like it when books make us feel smart.

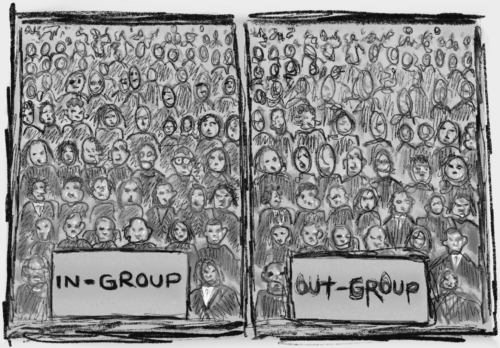

Yet referentiality is defined by the restriction of its audience; with every allusion, there’s an in-group and an out-group. Perhaps my choice not to mention Sontag in Humanities 10b was the right decision—identifying her by name would only have made my point less accessible. Why name-drop needlessly? Moderation is key—the best references, I’ve learned, clarify rather than obscure; they democratize rather than preclude.

IN: Susan Sontag

OUT: Blood Oaths

Now that’s how you do a reference.

Jules Sanders (julessanders@college.harvard.edu) wishes that there were a course offered at Harvard on the essays of Susan Sontag.