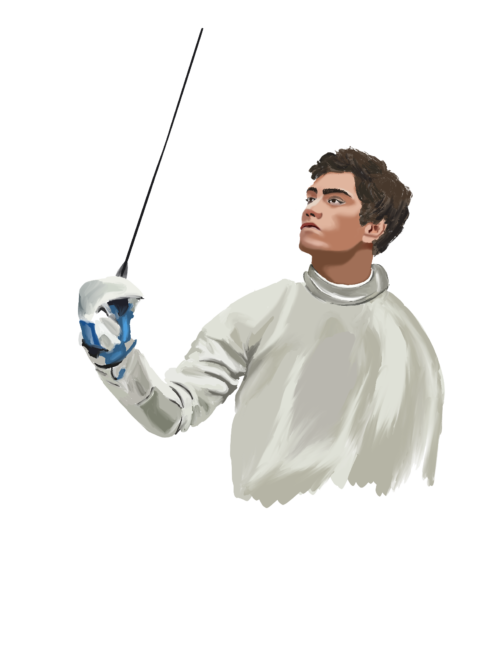

Mitchell Saron ’23 has loved sword-fighting since before he can remember. An early introduction to the Star Wars and Lord of the Rings franchises stoked that fire, leading Saron to attempt to duel everyone in his life: “I had this huge lightsaber and toy sword collection, and I would always ask [my parents] to fight with me in the yard.” His enthusiasm eventually got to the point that Saron’s mother was struggling to stop him from running around the house with swords by third grade.

Luckily for Saron, his mother unsuspectingly stumbled upon the solution. “She was complaining to her doctor, and she was like, this kid’s driving me nuts. And the doctor’s like, ‘One of the top clubs is right by you guys.’” Upon walking into the club for the first time and seeing each of the three weapons, Saron knew this was the sport for him. He dropped all other athletic commitments and began his journey towards becoming an Olympian.

Saron traded his lightsaber for a real sabre after learning about the three distinct fighting styles for fencing epee, foil, and sabre. For epee, fencers can hit their opponent anywhere on their body, but it can only be a poke. Foil has the same rules about the type of touch, but the target area is restricted to the torso and back. Saron describes a sabre “like a real sword” that is slashed at the opponent’s upper body and head, similar to Jedi duels, but less deadly. Sabre bouts are divided into three three-minute periods, with each fencer hoping to achieve 15 touches before the nine minutes are through. If no one has reached 15 touches by the end of the allotted time, the winner is the competitor with the most touches.

Like most amateur athletes, Saron has always dreamed of competing in the Olympics. After becoming part of the USA fencing pipeline through Cadets at age 14, he began to age through the system, leaving Cadets at age 17 to compete with the Juniors as a U-20. At age 18, he began to realize that competing in the Olympics could be a legitimate possibility after his success at multiple tournaments. In addition to his involvement with international fencing, Saron also pointed to his watching the London 2012 Summer Olympics as the starting point for his Olympics journey.

“I went to London with my dad and my sisters to watch, and I saw Olympic fencing for the first time when I was 11. I got this bracelet, and I didn’t take it off. It’s just London 2012; I got it there, and I was like, ‘I won’t take this off until I qualify for the Olympics.’ I’ve had this on for a long time.”

To continue to develop as a fencer, Saron chose to take his talents to Harvard while continuing to compete on the international level. “Harvard had a track record of Olympic fencers,” he explained. “There was a trend of a lot of fencers continuing to do international fencing alongside collegiate fencing.” Many fencers stop any competitions outside of their university once they step foot on campus, so Saron knew that he wanted to be surrounded by other fencers at Harvard who were like-minded in their competitive drive to hopefully contend for Worlds and Olympic spots.

Saron was also specifically drawn to Eli Dershowitz ’19, the Crimson’s assistant coach and two-time Olympian representing the U.S. in sabre fencing. Dershowitz is heavily decorated both collegiately and internationally, winning two individual NCAA titles during his four-year All-American career in addition to his U.S. national and world championships. In addition to coaching the Crimson, he continues to compete on the international level and trains with Harvard athletes. A childhood idol of Saron’s, the relationship came full circle when both were named to the Olympic squad.

After graduating from Harvard in the spring of 2023, Saron moved back to New York to begin training full-time with hopes of making the Olympic sabre team. The qualification process for Paris required Saron to be one of the top four fencers in the country by April 2024; in non-Olympic years, the top four fencers head to the Pan American Games and World Championships once they are named to the squad. For his preparation, Saron was bouting almost every day, on top of taking private lessons with his coach, attending conditioning sessions, and cooking all of his meals. His hard work paid off when the team was announced, and to his shock, all four members of the squad were current or former Harvard athletes.“It just felt so cool that it was the four of us. The four of us had such personal connections with one another,” Saron stated.

Saron came into the individual competition ranked 17th in the world; similar to March Madness, upsets are extremely common, so initial ranking does not make or break the chances for medaling. His first opponent was against Maxime Piafette of France. “My heart was beating out of my chest. And then they called my name, and I ran out and it was very loud.” His opponent then entered the arena and the volume exploded. After beating Piafette 15-12, he took his mask off and shushed the French contingent in the crowd.

Following a close loss to number one seed Ziad El Sissy of Egypt in the round of 16, Saron stated, “I had to fence the number one in the world, and I lost 15-13 which is obviously super disappointing [and] painful, but I thought I did the best I could.” He then turned his focus to the team event, where the team had been extremely dominant throughout every competition in the last year. “The last nine international tournaments before that, we meddled at every single one, and we got gold in five.”

In a shocking upset, the U.S. men’s sabre team fell to Iran in the opening match 45-44; Saron was in disbelief that a team poised to win a gold medal had their Olympic dreams dashed so quickly. “I would have been disappointed with a bronze because I thought we were so good. It was crazy to me, because I was like, ‘How could this have happened?’ This is the perfect amalgamation of everything coming together. And then we lost.”

Despite an unexpected ending to his time as an Olympian, Saron is extremely grateful for the opportunity to represent the U.S. on the ultimate world stage. He is planning to spend time with friends and family in addition to allowing his body to heal before beginning to fence again. While he may not have a gold medal around his neck, he still wears the London 2012 bracelet as a reminder of the dream he was able to fulfill and the power of following through on your commitment to a goal.

Kate Oliver ’26 (koliver@college.harvard.edu) used to have lightsaber duels with her younger brother.