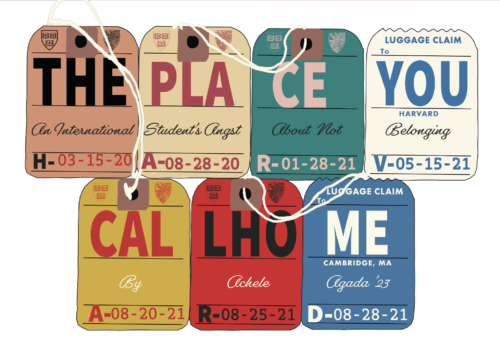

Moving across the world to ‘find yourself’ is not a clever paradox.

We moved from Nigeria to England in 2001, mere months after I was born. My parents immigrated, taking with them three young children (and an incredible resolve), in search of increased opportunity and stability. I often explain how I was raised in a traditional Nigerian household, entrenched in Nigerian culture, morals, and rules—it just happened to be situated within a very white and middle-class neighborhood in the north of England.

Being a Black, female immigrant has meant I have always battled with belonging. Growing up, I wasn’t like the typical white kids who predominated my classes and dictated the norm, but I also differed from the few other POC kids whose families had lived in the United Kingdom for generations and were surrounded by communities of culture. This understandably led to a perpetual identity crisis and I quickly chose to dissociate from my surroundings and locate my being in an ethic of hard work. In many ways, I’ve always felt like an international student, away from home, learning how to thrive in a foreign environment, determined to make something of myself. Maybe that is why it was so easy for me to pack up and move across the Atlantic for a chance to tough it out and see what I could produce.

In the fall of 2019, I embraced a new life within Harvard Yard. I arrived bright-eyed and full of energy, looking to finally find my place in the land of opportunity. It’s not that I believed America was without fault; I knew all too well of the long and continued history of struggle and pain in the United States. Still, I had bought into the American dream, donned my visa status with pride, and fought my way to Harvard. Like many international students, I believed that once I graduated from these hallowed halls I would be unstoppable. I believed that if I could find my feet at the best University in the world then along the way I would also find myself.

I had not quite ‘found myself’ by March 15th, 2020, when instead I showed up at a deserted Logan International Airport, heading back to England for the indefinite future. COVID-19 had thrown everything into disarray. I boarded my long flight back to Europe with another international friend, and as we watched sad movies on our undersized screens and sobbed together on the empty plane, I worried about what this all meant for my American adventures in self-discovery. I did not know then that I would not see campus or the life I had begun to curate here until the next year.

For much of my time back in England, I was in strict lockdown. Being stuck in my small Yorkshire town triggered memories of a previous life categorized by loneliness and a need to escape. I became extremely anxious, consistently refreshing the CDC’s website on travel policies, tracking the pandemic death count, and desperately planning my return to campus. The whiplash of being back in Britain was not something I had prepared for, and only then did I begin to realize how misguided it was to situate my hopes of belonging along the cobbled streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

I sank into a slow, burning depression fuelled by my refusal to accept where I was. For 10 months I lived on Eastern Standard Time and ignored my family around me; I existed on Zoom more than I existed in reality; and longed to be back at Harvard. But public health experts dictated a shut-in, and I was shut out. Helpless, I watched as America went on without me. It was there, from the outside looking in, that I was forced to turn a critical lens on the rosey facade I had constructed.

The truth of the matter is that as the pandemic escalated, Harvard would not protect me, and the U.S. gladly pushed me away. I, alongside many internationals, had been banned by the US.. government from entering North America with no indication as to when I could return. When making plans for the fall of 2020, international students were an afterthought that the University seemed to not consider in their calculations. Foreign first-years were given the very worst hand. We were made to choose between a digital college experience divorced from the thing we all claim is the best part of Harvard—its community—and taking the year off, wondering what could have been and what was to come.

Like the rest of my sophomore class, I was not invited to return to campus that fall and chose to fiercely advocate to enroll in Harvard’s Study Away program. In the fall planning announcements released last August, the University hadn’t considered how international students stuck in distant time zones would manage a full year of online learning. I began a frantic search for solutions. After corresponding with the Harvard International Office and the tutors at St. Catherine’s College at the University of Oxford (who were willing to accept late applications from a number of desperate Harvard Brits), I was able to study at Oxford instead of committing to a prolonged virtual reality from home.

While I attempted to navigate this unfamiliar environment, the Harvard administration did not check in on me and therefore did not notice as I slowly began to drown, left alone at a locked-down Oxford. I was exhausted and drained from the previous summer of 2020 when America imploded at the hands of police brutality, racial disparity, and institutionalized suffering. I felt disillusioned as I saw people, just like me all across the world, marginalized and discarded by the systems of capitalism that profited from their downfall. During a year of both experiencing and observing many hardships, I became acutely aware of how unwelcome I was in both British and American society. This realization made me question why I had thought Harvard was a place I could ever belong.

On January 26th, 2021, I flew back to Boston. The U.S. amended its travel ban to allow those with pre-existing student or work visas, alongside a negative COVID-19 test, to return to the country. With this slight rule change in place, Harvard allowed me to re-enroll and pay the spring semester’s tuition, room, and board. I was so grateful to finally be back in the dorms that missing my sister’s 22nd birthday on the day of my flight seemed like a worthwhile sacrifice. Besides, I reasoned, if circumstances had been normal this past year, I would have missed many important family holidays while living on a different continent.

But back in Cambridge, with a strict no-outside-guests policy, Zoom school, and takeaway meals eaten alone in my Dunster House suite, I did not feel at home. Living under the administration’s constant surveillance with nothing but the bone structures of college life left me feeling institutionalized and longing for my sisters’ jokes and familiarity.

Since I returned to Harvard’s campus six months ago, I have not left. Students have come and gone, COVID-19 restrictions have steadily eased, and the air around me is now one of anticipation for a ‘normal’ return in the fall. Yet trepidation builds as the virus mutates and cases rise once again. News of earthquakes, terrorism, and mass shootings suggest continued turmoil across the globe. This summer I wasn’t able to return to England due to disruptive travel quarantine periods and an underlying concern of increasing the risk of infection to my family. Instead, I took three Harvard research positions, grieved the death of my maternal grandmother thousands of miles away from my own mother, and missed more birthdays.

Somedays I am able to feel like I have finally settled in and know my place at Harvard. Other days I feel terrified and unsupported; I miss my family and regret treating them with disdain. As a result of the pandemic, my relationship with the U.S. has irrevocably changed, and my status as an international student now rests heavily on my mind.

As I look at the landscape of elitism, wealth, and individualism I opted to immerse myself in, I loathe the politics, the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality, and the selfishness of it all. The label “international” is no longer one I wear with pride. Instead, it reminds me that I chose to leave behind everything I knew and take the financially and logistically irresponsible path of going to school an ocean away. I cannot help but wonder if the sacrifices I made to be here will even be worth it. Did I cage myself into a life in the fast lane, with no time to worry about feeling at home?

I wonder if my parents ask themselves this same question when reflecting on their move from Nigeria. I’m sure they miss their home back in Africa and the community they traded in for the nuclear family model and a chance to make it in the Western world. Maybe that is why they had transported as much Nigerian culture over with them and made sure that my sisters and I knew we were not like the other kids in our small English town. All I know is that I am here now and I cannot let my time here go to waste—somehow I have to find a way to bring my summed experience along with me, and make wherever I am feel like home.

Achele Agada ’23 (oagada@college.harvard.edu) is rediscovering home.