This summer, I interned at a bank. I lived with six MIT students: three incoming seniors (four, including myself), and three recent graduates. The majority of us worked in finance, whether it be for a summer internship or having a full-time job, and the final roommate was a software engineer. The difference between being a student and an intern was stark, as were the perspectives on life from my Harvard friends and those that I worked and lived with.

One weekday night, when a lucky handful of us were home from our deskjobs and the others were getting ready to embark on yet another 13-hour office day, we were entertaining our usual evening routine: preparing our pre-prepared Trader Joe’s dinners, coming back from the gym, and debriefing our days, searching for anything that could help us distinguish one day from the next. This particular evening, one of my younger roommates was asking a recent college graduate for advice on her classes.

I concentrated hard on the conversation, making out what I could of the cacophony of numeric class names and my roommates’ respective opinions of them. From my understanding, 18.435J was obviously more applicable to real-world investment strategy than 18.510, and 15.068 would better suit you for 15.074J than 15.007J. Obviously.

I was dumbfounded. I don’t think—and perhaps it’s my idealistic and ignorant perspective of my education—that I’ve ever chosen a class based on its utility. In an interview for an OpEd I wrote my sophomore year, my advisor Keith Raffel urged me to not consider my college education as a stepping stone towards the next internship or professional opportunity, but rather to enjoy and embrace all that Harvard had to offer. From my understanding, our conversation surrounding the myopic ambition that led to this calculated college experience was unique to Harvard students—or those at similar universities.

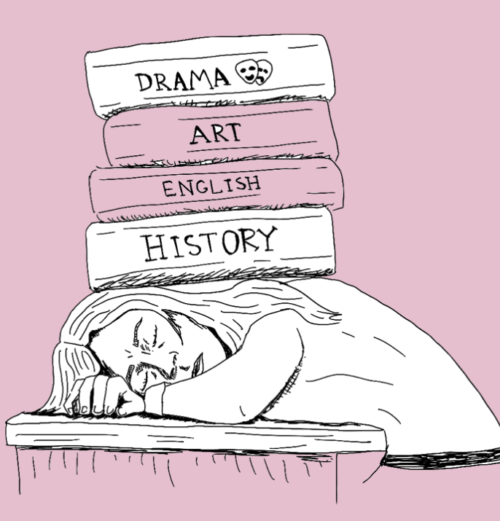

Perhaps my experience at Harvard has been blissfully ignorant, allowing me to dive head-first into numerous history, English, and theory-based courses to satisfy my desire to discuss diverse perspectives and ideas. But my encounters this summer with roommates, coworkers, and other similarly positioned students my age harshly drew me out of this trance. The real world is tainted with the obligation of practicality.

Traditionally, banking internships require a manicured background of finance, accounting, and statistics and are opportunities that most of my coworkers had been preparing for the majority of their academic university careers. (It is a privilege of Harvard, I must add, to be able to study non-finance majors and still be met with finance opportunities). Dozens of introductory conversations exposed the fact that I was one of the few humanities majors (I can remember one other student in my intern group of 50+ who studied philosophy). Each other student, like my roommates, elected their course loads and majors based on something much more practical to the work we were doing. Finance, real estate, accounting—I even met someone who studied supply chain.

In conversation with my older brother—a Harvard ’22 economics concentrator who now works at an AI startup, I reflected off my social and professional observations from my peers. Few had hobbies outside of work, and every single conversation, whether it be at dinner, drinks, or even Sunday morning brunch, revolved around work. His response: “Sometimes I wish I went to MIT. It’s just so much more practical.”

It’s true. Harvard’s liberal arts education offers very few pre-professional academic opportunities. Its lack of pre-law, finance, and political science programs forces students to engage with theories and subjects that don’t necessarily give them applicable technical skills for a corporate setting. In a way, our four years at Harvard—even if a student studies majority economics, computer science, or statistics courses—are shielded from the realities of corporate obligation.

An alternative approach, and one that is much more common just two miles east at MIT, focuses on providing students said skills to solve real world problems, such as those of corporate America, rather than learning about the different methods to approach, analyze, or manage them. However, technical programs at schools like MIT which focus and support the election of specific majors, while likely giving graduates a more defined sense of their determined career path, can easily fault in their disregard for pure curiosity.

Another night, my roommate became rather confused by a comment I made. Sitting at opposite ends of the kitchen table working, I remarked that it felt like I was doing my readings at the dining hall—something that monopolized most school nights and garnered a strangely charming sentimentality. Why would I ever spend time doing work on an assignment, he wondered, if it did not directly and immediately impact my grade?

I thought my response needed no explanation; I study history because I love it, even if it seems to offer little practical value. But I think that is something that Harvard has taught me to cherish—readings, writings, and conversations that might not provide any active use but a reverence for academic curiosity and the centuries of wonder that came before me.

The unfortunate reality is that to be able to dive into subjects or fields of interests for the mere sake of doing so is a luxury that few people can enjoy. Speculating the meaning of consciousness in a 12-person social studies seminar will not prepare you for your management consulting case interview, a reality that filters out most students who dedicate their college careers to ultimate financial prosperity. What it will do, and what that numerous studies have revealed, is develop students with the ability to communicate, empathize, and consider alternative perspectives—all relatively soft skills, but vital to productive work and team environments.

But the opportunity costs between curiosity and lucrativeness are found everywhere, not just in a college summer apartment. Reading novels versus personal finance books, listening to music versus informational podcasts, and working at a job that caters to genuine interests versus a bureaucratic one determine the makeup and class divisions in the world we live in. Those who professionally pursue their passions of less productive enterprises are in a way, punished for not contributing more to the economy.

Few kindergarten children, when asked what they want to be when they grow up, answer financial advisor, private equity investor, venture capitalist, or any of the other niche professions that both govern our global economy and are so highly sought after at my age. This shift in life purpose then becomes one of practicality rather than genuine curiosity. And there is no direct person or community to blame, other than the mere value that our world places on certain professions. Maybe one day we can live up to our kindergarten dreams without worrying about the opportunity cost of doing so.

Marbella Marlo ’24 (editorinchief@harvardindependent.com) is the Editor-in-Chief of the Harvard Independent.