A conversation with indie rocker and writer, Mikel Jollett, about his memoir and accompanying album, Hollywood Park

In the smoky ambience of standing-room-only, I stood on my tiptoes, straining for a glimpse through a sea of shoulders as The Airborne Toxic Event took their positions on the stage. A certain hush hung over the art-deco, hardwood-meets-cashmere of the El Rey Theatre, a mere six miles from the Los Angeles neighborhood of Silver Lake, the indie band’s familiar stomping grounds. Glimmering chandeliers framed the band members with a certain rock-and-roll elegance, as frontman Mikel Jollett announced that the band would be performing new music. He asked that we not instinctually grab our phones to capture this work-in-progress, and instead, to be present. It was an exchange of trust: he trusted us not to release recordings, and we trusted him that, yes, one day we would come to hear these songs again. The songs performed that night in late March 2017 would become the soundtrack to his just-published memoir, Hollywood Park, a forty-year odyssey following his life from escaping the commune-turned-cult, Synanon, with his mother, to establishing new roots in California with his father. Together, with his father’s support, they earned his acceptance letter to Stanford University, and later Jollett would go on to begin a successful music career, founding the band The Airborne Toxic Event.

How a musician becomes an author

In many ways, his first exposure to music happened shortly after his mother, Gerry, picked up Mikel and his brother, Tony, from the Synanon compound in Tomales Bay, California. Mikel describes her as the woman he’s told to call Mom; all the children of Synanon lived in this compound together, collectively orphaned from their parents. The three of them escaped and moved into an apartment in East Oakland. A record player was their most valuable item, filling the otherwise empty room with the warmth of vinyl, the needle pulling out melodies from Bob Dylan to Tchaikovsky.

They eventually moved to Salem, Oregon. During the fifth grade, Mikel met his best friend Jake. They both were familiar with the hardships of poverty, exchanging food stamps for rubbery yellow government cheese. In an afternoon hang-out, Jake played the record Three Imaginary Boys by The Cure, introducing Mikel to this rock god they call Robert Smith. These moments opened his eyes. Jollett shares with me, during my phone interview with him, that it sparked this realization that these two poor kids from Salem could “create an identity, and there’s this whole world out there of art and music and songs.”

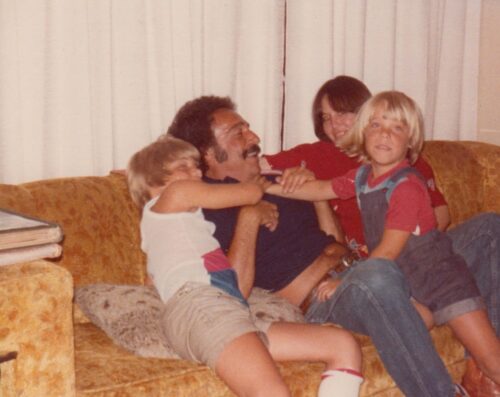

Young Mikel, after escaping from the cult Synanon. Photo courtesy of Mikel Jollett.

“That was my introduction to literature. There’s a straight line from hearing ‘The Head On The Door’ and eventually reading the Nabokov catalog,” Jollett tells me. “There’s a straight line from ‘The Queen Is Dead’ by The Smiths to Beloved by Toni Morrison.”

His Grandma Juliette gave Mikel his first acoustic guitar, he recalls in his memoir. Strumming its worn nylon strings, he would play the chords to “Space Oddity” by David Bowie, the strange man with a spaceship that seemed so exotic compared to Mikel’s four walls. Music could be a way to write his way out of his past. And so, he became a performer—both on stage, but also in his life, as he created new identities for himself. For each show, for each city, he would put on these masks to the world—and it just got exhausting.

“By the time I got off the road after my dad died—I’d been on the road for years, and I was over it. If you told me at the time I wouldn’t play another show, I’d be fine with that. I was over it, so burnt out… and then, those residencies were great,” Jollet shares with me, over three years after The Airborne Toxic Event’s four-show residency at the El Rey Theatre where they debuted new songs that would be released on the album Hollywood Park.

His father’s death destroyed him. He began penning songs not to perform, but to grieve. Jollett likens this song-writing process to “that idea from mythology: we write songs in order to tell the stories in our lives that feel most overwhelming and important.” The experience was not catharsis, per se, but it helped him get a grasp on this new world without his father. “Everything I Love Is Broken,” the seventh track on the new record, was one of his first compositions—the opening lyric of its second verse is the same as the memoir’s opening line: “We were never young.” After nine months, he decided to begin writing his memoir. Jollett recalls, “I worked twelve hours a day, six days a week… there was almost a good solid year where I didn’t do a single thing. I didn’t do a social event, and I didn’t do anything but write… it was a running joke with my wife and me. She was just like, ‘Dude, you’re kind of losing it!’”

Left: The cover of Mikel Jollett’s memoir, Hollywood Park. Photo courtesy of Celadon Books.

Right: Mikel Jollett, indie rocker and author of Hollywood Park. Photo credit to Dove Shore.

He continued writing songs while writing the book. The memoir is broken into four sections, each with its respective voice. Jollett says, “Each one has different grammatical structures, different sentence structures, different attitudes—capturing the voice of a precocious five-year-old, eight-year-old, twelve-year-old, and adult writer.”

“While I was writing the book… I was so in the world of my child self, and I spent so much time trying to recreate the world,” says Jollett. “So, I wrote songs from that perspective too. It wasn’t something I’d ever really done before. It also just felt right.”

I can hear this child’s voice in his songs “All The Children” and “I Don’t Want To Be Here Anymore.” In his chapter, “The Men Who Leave,” Jollett describes a moment in his childhood home in Salem, wrought with tension, when Doug, Gerry’s boyfriend, pins Mikel onto the floor. Mikel escapes on his bike, as he makes a mental list of all the reasons why he could run away. He could become a boy of the wilderness, with leaves as a blanket to tuck him in at night. A song soon revealed itself to him. “Come On Out,” the fourth track on the record, culminates with the lyrics, “Break my fall,” the same desperation clouding young Mikel’s mind, as he gazes down from a bridge into the water below. He wonders, “What breaks your fall?”

“I’ll play my role, and you’ll play your part”

He finds his answer in a seedy racetrack called Hollywood Park. During junior high, Mikel moves in permanently with his father, Jimmy, and step-mother, Bonnie, in their Los Angeles home. On Sundays, his father took him to this racetrack, where the scents of horse manure and cold beer meet the meal of champions: corned beef sandwiches, Sprites, and Carnation chocolate malted ice creams. On the accompanying album’s title-track “Hollywood Park,” Jollett also brings the soundscape of the racetrack to life again. Much like the blurred words of a track announcer, a man’s indiscernible words boom amidst the crescendo of electric guitar. “Memory’s like a string, and you begin to pull on it,” Jollett tells me, and about thirty seconds in, I think I hear that string finally pull through. The drums, imitating the speedy gallops of horses racing, usher in the beginning of this epic six-minute overture. Jollett sings, “A73-581 was the number, they burned it in my brains… we could run.” Considering how the song’s an ode to a racetrack, at first it seems he’s referring to the colorful numbers regally draped over the sides of racing horses, used for bets to be placed and won. (In the memoir, he warmly remembers when his father got a payout after winning a bet—they celebrate with dinner at a Mexican restaurant, complete with deep-fried strawberry ice cream.)

Mikel, right, with his brother Tony. Photo courtesy of Mikel Jollett.

Instead, he’s singing about his father’s prisoner number assigned to him during his sentence in Chino state prison. Growing up, Mikel felt like he couldn’t escape his father’s ex-con past, which constantly cast shadows onto his future. When he studied hard at Westchester High School, his hard-earned praise was met with mocking pats on the back, remarking that he was finally getting it together: the first Jollett man to have a real shot at college. When he began his studies at Stanford University, he found himself incapable of answering his peers’ seemingly simple questions. What is your family like? What do your parents do for a living? Mine went to law school! Mikel quickly realized that the unedited truth of his family’s past wouldn’t cut it. What was he supposed to say? Jollett imagines his responses: “My dad managed a mechanic shop,” or “Well, I was born in a commune that became a cult called Synanon.”

Jollett tells me, “I think a lot of people do this. You word which parts of the narrative of your life you’re going to tell people and which parts you’re going to hide.” He admits that he didn’t bring up Synanon to a single person after age thirteen, emphasizing how he just “wanted to present this other face to the world,” rid of his family history.

Mikel graduates from Stanford University. Photo courtesy of Mikel Jollett.

“That’s part of why I called the book Hollywood Park. Part of it is that it’s a place—it was a racetrack—but it’s the idea of Hollywood, of playing your roles in your life,” says Jollett. “The theme of the book is about performing. It’s about learning to just act out what I thought other people needed to hear from me… I learned how to get attention from the adults when you live in an orphanage: you act, you play, you perform. You learn what the adults want from you: be cute or be precocious, seem like something about you is magical.” After graduating from Stanford, he continued on with this acting, playing, and performing. He couldn’t keep a relationship, resulting in him singing his romantic failures to the faceless crowds. As Mikel got tired, his father got sick.

“Someday they’re gonna write about us, living here in the shadow of this gathering dust… here, in California”

Destruction strikes all at once. Within three weeks of each other, Mikel’s father dies, and the seedy racetrack of Hollywood Park gets torn down. As the grandstands are destroyed by fiery explosions, his father’s body is cremated. Both are reduced to ash, and the cruel reality begins to settle much like a cloud of gathering dust. This elusive, complex concept of family, of love, that Mikel spent his whole life either chasing or running from—he had found it here at the racetrack, in the simplicities of admission tickets and shared meals from the concession stands. His father and the racetrack, though physically gone, still exist. “Toni Morrison has this wonderful idea of rememory,” Jollett tells me. “The idea is that memories don’t disappear. They’re still existent in places.” Even when they no longer stand, their memory remains.

I think this is the most brilliant part about Hollywood Park: its cruel acknowledgment that, yes, maybe we all do end up as dust, but maybe it doesn’t have to be such an ashen truth. Instead, we can celebrate this racetrack and family and fatherhood with all of the thundering glory of horse hooves and rock-and-roll. That’s the conclusion I’ve come to, reflecting back to that night three years ago at the El Rey Theatre, as Mikel sang these songs with newfound meaning—finally bereft of performance for the sake of performance, of playing his part. Instead, Mikel now sings to bereave and honor his father’s memory. As soon as I turned the last page of his memoir, I reached that same conclusion.

Mikel (left) with his father and brother Tony. Photo courtesy of Mikel Jollett.

Jollett successfully adapts many magical and timeless elements from the classics and mythology alike: mainly, with Homeric bonds between fathers and sons. Yet, in two songs recorded nine years apart, Jollett accomplishes his most seamless adaptation of the Greek and Roman tradition: consecrating his lost loved ones in the sky, where mythology and astronomy intertwine. In “The Graveyard Near The House,” Jollett’s lyrics promise his loved one: “If you die before I die, I’ll carve your name out of the sky.” In the latest song, “Hollywood Park,” Jollett celebrates his father, singing of them “writing their names in the sky.” Stars wrote the history of heroes past, immortalizing luminaries of the times for their valiance.

I cannot help but think that this may be even more rebellious than Jollett storing away his father’s ashes in a paper soda cup, spilling them to find new life as dust on the Santa Anita racetrack. He writes in his memoir, “More often than not, the people we admire publicly are rarely the ones we privately love the most,” but he nonetheless defies these boundaries of how we can memorialize the ones we love privately. By writing Hollywood Park, Jollett also writes his father’s name, for all to see, in the sky we live under together.

Marissa Garcia ‘21 (editorinchief@harvardindependent.com) thanks Mikel, for being to her what David Bowie was to him.

The Harvard Independent received an Advance Review Copy of Hollywood Park, courtesy of Celadon Books, a division of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC.

You can purchase your copy of Hollywood Park, both the memoir and album, here.

This interview has been edited for purposes of length and clarity.

Header Image: Mikel with his brother Tony, father, and step-mother. Photo courtesy of Mikel Jollett.