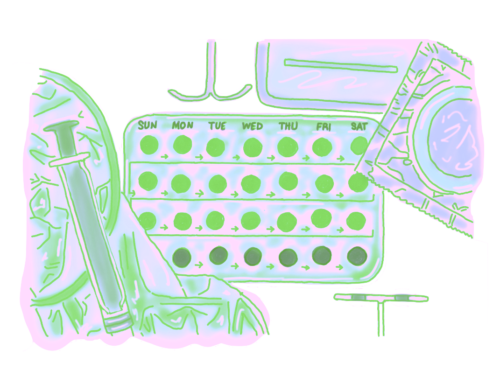

None of us want to get pregnant, but a lot of us want to have sex. This is the age-old catch-22 for a college student with a uterus. The solution? Birth control—the miracle pill. Take it once a day, and all of your fears will be resolved, they say. But at what cost?

Sophie O’Melia ’25 says that on her old birth control pill, she “felt mentally heavy and emotional all the time.” It took multiple rounds of trial and error to find a form of birth control that worked well for her body. Julia O’Donnell ’25 says, “Whenever I forget to take [my pill], the next day I’m super nauseous all day or I have a really bad headache. It just throws off my week.” O’Donnell notes that many of her friends have experienced symptoms, particularly depression and weight gain. Despite these self-reported side effects, studies show that those who hope to avoid an unintended pregnancy are willing to take their chances.

According to the CDC, 64.9% of women between the ages of 15 and 49 are currently using some form of contraception. With over 72.2 million individuals pursuing options to avoid pregnancy, one would hope the science and resources available were informative and conclusive. Unfortunately, most perceived side effects of contraception are strictly anecdotal, regardless of how widely they are experienced. Research on the effects of hormonal contraception is sparse and contradictory. One study on the population of Denmark concluded that the use of hormonal contraception was linked to future use of antidepressants, while another study from Northwestern found the exact opposite. Regarding these discrepancies, O’Melia says, “everyone has a different experience [with birth control], so I don’t so much believe the research online because everyone is going to react differently.”

Dr. Huma Farid, Harvard Medical School affiliate and Associate Program Director of OB/GYN Residency at Beth Israel Hospital, delineated the facts and fictions of hormonal contraceptives. Farid says the most common side effects of hormonal birth control are “headaches, some bloating, [and] some nausea,” but notes these symptoms “tend to go away after the first couple of months of use.” One of the most common questions she receives from patients is, “is my birth control going to make me fat?” Farid reports that aside from slight weight gain associated with the shot, “there have been multiple studies showing that no birth control causes weight gain, with the exception of some water weight that will go away after about three months.”

Regarding the association between anxiety and depression and hormonal contraception, Farid says the research is conflicting. “There are some studies that suggest that adolescents… being prescribed birth control for the first time may experience more depression or have higher risks of depression,” she explains. “But you also have to wonder, when is depression normally diagnosed? As a teenager, right? So it’s hard to tease out.”

The National Institute of Health pours $42.2 billion dollars into medical research per year. Despite women making up over 50% of the population, only $5 billion of this sum is directed towards women’s health. This lack of funding prevents widespread, conclusive research from being conducted and shared, which compounds the confusion and fear toward the impact of different medicines on women’s bodies, beyond just birth control.

Pregnant women are deemed a vulnerable patient population and are thus excluded from many research trials. This impedes the data available on the effects of medications on pregnancy. For example, when the COVID-19 vaccine became available, it was not approved to be tested on pregnant women. Many of Farid’s patients refused to be vaccinated without such research. “COVID-19 has really highlighted all the ways in which not incorporating women and not incorporating pregnant patients into trials has impacted science and our ability as physicians to advocate for what we think is the right thing,” Farid says. This exclusion “really does hurt women, because now I’m trying to convince my patients to get the vaccine, but people don’t really trust their physicians, then there’s no data, so people are really reluctant.”

The lack of information about types of birth control, and the plethora of knowledge about their widely experienced side effects, make women across the country reluctant to try it. Farid notes that 50% of pregnancies in the US are unintended. “I think that in the public perception, patients don’t like to use birth control, and feel that there are a lot of side effects they cannot tolerate.” For example, Niara Botchway ’23 says she has “met so many people that have had bad experiences,” that she chooses not to use hormonal contraception. “There are no good options for me,” she says.

To rectify this distrust and protect from unwanted pregnancies, “men should have a role to play in this as well,” says Farid. A new non-hormonal male birth control pill is soon to begin human trials. If this form of contraception enters the market, will it lighten the burden of responsibility that falls upon women in preventing pregnancy?

According to Matthew Nekritz ’25, “I think it is going to be really hard to break that expectation down because of men’s perceived threat of birth control, such as, ‘Will this mess with my hormones? Will this affect my mood?’—everything that women constantly have to deal with being on birth control.” O’Melia agrees: “I think [men] would still believe it’s more the girl’s responsibility. They’d think, ‘Oh, it’s so new. We don’t have enough research.’ Even though, in reality, there’s not that much research on female birth control as well.” The perceived responsibility of preventing pregnancy continues to fall mainly on those who stand the risk of getting pregnant.

When choosing the right form of contraception, it is important for students to research their options and consult a medical professional. For information on how to find resources for contraception here at Harvard, contact Harvard University Health Services.

Lauren Murphy ’25 (ljmurphy@college.harvard.edu) is researching the copper IUD.