A Presidential Candidate Speaks Boldly after Debates

By JOSE ESPINEL

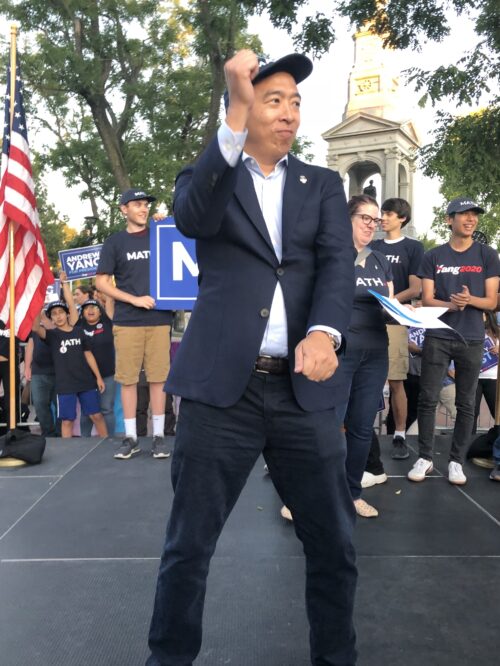

In the heart of Warren country, a different candidate danced onto the stage. Andrew Yang arrived at sunset and addressed a crowd of several hundred in Cambridge Common. Most were young. A group of high school volunteers in the front row arrived an hour early to paint posters. T-shirts from MIT and Harvard were common. Above the gathering danced the bold “Math.” placards that have become, to use the appropriate millennial parlance, a meme.

Yang reminisced his college days at Brown in his opening remarks. “[Boston] was our Vegas… I love New England… I’ve been all over and now I’m back.” The Democratic candidate then pivoted to politics, asking the assembly “where revolutions start,” to which they replied “Boston!”

Standing on the same ground where Washington once convened the Continental Army, Yang called for a new revolution, “a revolution of reason.” He sees himself leading the charge. Armed with math and an outsider’s perspective, he aims to bring Silicon Valley disruption to Capitol Hill.

In Yang’s eyes, policymakers have struggled to keep up with rapid technological progress in the early 21st century. Automation killed jobs faster than retraining replaced them. The unemployed and disaffected casualties of a shrinking manufacturing sector looked to the government to help them in their hour of need — finding no one would listen, they were forced to look to an outsider to carry their voice. In 2016, they found that outsider in Donald Trump.

According to Yang, the media misdiagnosed the cause of Trump’s ascent. “Facebook, Mitch McConnell, there’s a whole cocktail of reasons the press puts out there [for why Trump won]… but they haven’t looked into the numbers. I dug into the numbers and the numbers tell a very clear and distinct story. The numbers say that the reason why Donald Trump is our president is that we automated away 4 million manufacturing jobs in … swing states.”

Yang claimed automation is just getting started, “now what happened to those [manufacturing] jobs we’re now going to do to the retail jobs, call center jobs, the truck driving jobs, and on and on throughout the economy.”

Claiming many of his friends in Silicon Valley are investing “165 billion dollars a year” to automate the trucking industry, and that they are “95 percent of the way there,” he estimated some 7 million trucking jobs may soon be eliminated, with roadside diners and service stops also caught in the crosshairs. With AI use cases maturing fast, Yang argues that increasing the minimum wage would only further incentivize automation and leave more Americans out of the workforce. Yang’s alternative solution is the Freedom Dividend. His campaign website defines the policy as “a universal basic income of $1,000/month … for every American adult over the age of 18.” Yang intends to model the Freedom Dividend after Alaska’s Permanent Fund, taxing the vast coffers of American technology companies instead of oil revenues.

In 2020, Yang hopes voters find a new outsider in a Silicon Valley entrepreneur fond of PowerPoint, frank language, and skipping out on ties. It may not be reflected in the polls, but long after the sunset on this one day in Boston the energy was still all there, all for Yang.

Jose Espinel ‘20 (espinel@college.harvard.edu) enjoys examining how politics engage and interact with Harvard and the surrounding community